本文使用 Zhihu On VSCode 创作并发布

原文:A Year of Spaced Repetition Software in the Classroom

作者:tanagrabeast

2015 年 7 月 5 日

Last year, I asked LW for some advice about spaced repetition software (SRS) that might be useful to me as a high school teacher. With said advice came a request to write a follow-up after I had accumulated some experience using SRS in the classroom. This is my report.

去年,我向 LW 征求了一些关于间隔重复软件(SRS)的建议,这些建议可能对我这个高中教师有用。在我积累了一些在课堂上使用 SRS 的经验后,我收到了一个要求写一篇后续文章的建议。以下是我的报告。

Please note that this was not a scientific experiment to determine whether SRS "works." Prior studies are already pretty convincing on this point and I couldn't think of a practical way to run a control group or "blind" myself. What follows is more of an informal debriefing for how I used SRS during the 2014-15 school year, my insights for others who might want to try it, and how the experience is changing how I teach.

请注意,这不是一个用于确认 SRS 是否“有效”的科学实验。先前的研究已经相当有说服力了,而且我想不出一个实际的方法来运行一个对照组或“蒙蔽”自己。下面是一个非正式的报告,介绍我在 2014-15 学年是如何使用 SRS,我对其他可能想尝试 SRS 的人的见解,以及这种经历如何改变我的教学方式。

Summary

摘要

SRS can raise student achievement even with students who won't use the software on their own, and even with frequent disruptions to the study schedule. Gains are most apparent with the already high-performing students, but are also meaningful for the lowest students. Deliberate efforts are needed to get student buy-in, and getting the most out of SRS may require changes in course design.

SRS 可以提高学生的学习成绩,即使学生不自己使用软件,甚至经常中断学习计划。对于成绩已经很好的学生来说,成绩的提高是最明显的,但是对于成绩最差的学生来说也是有意义的。为了得到学生的认可,需要深思熟虑的努力,而要充分利用 SRS,可能需要改变课程设计。

The software

软件

After looking into various programs, including the game-like Memrise, and even writing my own simple SRS, I ultimately went with Anki for its multi-platform availability, cloud sync, and ease-of-use. I also wanted a program that could act as an impromptu catch-all bin for the 2,000+ cards I would be producing on the fly throughout the year. (Memrise, in contrast, really needs clearly defined units packaged in advance).

在考察了各种程序,包括类似游戏的 Memrise,甚至是自己写的简单的 SRS 之后,我最终选择了Anki,因为它的多平台可用性,云同步和易用性。我还希望有一个程序可以作为我一年中临时制作的 2,000 多张卡片的临时收集箱。(相比之下, Memrise 真正需要的是事先包装好的明确的单元)。

The students

学生们

I teach 9th and 10th grade English at an above-average suburban American public high school in a below-average state. Mine are the lower "required level" students at a school with high enrollment in honors and Advanced Placement classes. Generally speaking, this means my students are mostly not self-motivated, are only very weakly motivated by grades, and will not do anything school-related outside of class no matter how much it would be in their interest to do so. There are, of course, plenty of exceptions, and my students span an extremely wide range of ability and apathy levels.

我在一所低于平均水平的美国郊区公立高中教九年级和十年级英语。我的学生是 "要求水平 "较低的学生,在这所学校里,荣誉班和高级预科班的招生人数很多。一般来说,这意味着我的学生大多不善于自我激励,对成绩的积极性很低,而且无论他们的兴趣有多大,都不会在课外做任何与学校有关的事情。当然,也有很多例外,我的学生在能力和冷漠程度方面的跨度非常大。

The procedure

过程

First, what I did not do. I did not make Anki decks, assign them to my students to study independently, and then quiz them on the content. With honors classes I taught in previous years I think that might have worked, but I know my current students too well. Only about 10% of them would have done it, and the rest would have blamed me for their failing grades—with some justification, in my opinion.

首先,说说我没有做什么。我没有制作 Anki 卡片,并把它们分配给我的学生独立学习,然后对他们的内容进行测验。对于我前几年教的荣誉班,我想这可能会奏效,但我太了解我现在的学生了。只有大约 10% 的学生会这样做,其余的学生会把他们的失败成绩归咎于我——在我看来,这有一定的道理。

Instead, we did Anki together, as a class, nearly every day.

作为替代,我们作为一个班级,几乎每天都在一起用 Anki。

As initial setup, I created a separate Anki profile for each class period. With a third-party add-on for Anki called Zoom, I enlarged the display font sizes to be clearly legible on the interactive whiteboard at the front of my room.

作为初始设置,我为每节课创建了一个单独的 Anki 配置文件。通过 Anki 的第三方插件 Zoom,我放大了显示的字体大小,以便在教室前面的交互式白板上清晰可辨。

Nightly, I wrote up cards to reinforce new material and integrated them into the deck in time for the next day's classes. This averaged about 7 new cards per lesson period. These cards came in many varieties, but the three main types were:

- concepts and terms, often with reversed companion cards, sometimes supplemented with "what is this an example of" scenario cards.

- vocabulary, 3 cards per word: word/def, reverse, and fill-in-the-blank example sentence

- grammar, usually in the form of "What change(s), if any, does this sentence need?" Alternative cards had different permutations of the sentence.

每天晚上,我都会写一些卡片来巩固新的材料,并及时地把它们整合到牌组中,供第二天的课程使用。平均每个课时 7 张新卡片。这些卡片有很多种,但主要有三种类型:

- 概念和术语,通常有翻转的配套卡片,有时补充“这是一个什么样的例子”的情景卡片。

- 词汇,每个单词 3 张卡片:单词/定义,翻转和填空例句。

- 语法,通常以“这个句子需要什么改动(如果有的话)”的形式出现。备选卡片上有该句子的不同排列组合。

Weekly, I updated the deck to the cloud for self-motivated students wishing to study on their own.

每周,我都会将这套牌组更新到云端,供希望自学的学生使用。

Daily, I led each class in an Anki review of new and due cards for an average of 8 minutes per study day, usually as our first activity, at a rate of about 3.5 cards per minute. As each card appeared on the interactive whiteboard, I would read it out loud while students willing to share the answer raised their hands. Depending on the card, I might offer additional time to think before calling on someone to answer. Depending on their answer, and my impressions of the class as a whole, I might elaborate or offer some reminders, mnemonics, etc. I would then quickly poll the class on how they felt about the card by having them show a color by way of a small piece of card-stock divided into green, red, yellow, and white quadrants. Based on my own judgment (informed only partly by the poll), I would choose and press a response button in Anki, determining when we should see that card again.

每天,我带领每个班级对新的和到期的卡片进行 Anki 复习,每个学习日平均 8 分钟,通常作为我们的第一个活动,速度大约为每分钟 3.5 张卡片。当每张卡片出现在交互式白板上时,我会大声读出来,而愿意分享答案的学生则举手。根据卡片的内容,我可能会在叫人回答之前提供额外的时间来思考。根据他们的回答,以及我对整个班级的印象,我可能会详细说明或提供一些提醒、助记等。然后,我会迅速调查全班同学对卡片的感受,让他们用一小块卡纸将卡片分成绿、红、黄、白四个象限,显示一种颜色。根据我自己的判断(只是部分地从调查中得知),我将在 Anki 中选择并按下响应按钮,决定我们什么时候应该再次看到那张卡片。

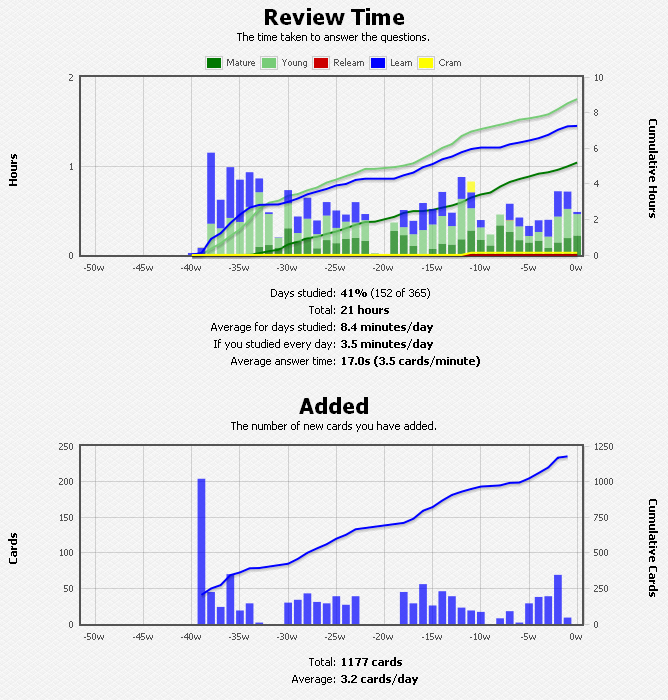

[Data shown is from one of my five classes. We didn't start using Anki until a couple weeks into the school year.]

[显示的数据来自我的五个班级之一。直到开学后的几周,我们才开始使用 Anki。]

Opportunity costs

机会成本

8 minutes is a significant portion of a 55 minute class period, especially for a teacher like me who fills every one of those minutes. Something had to give. For me, I entirely cut some varieties of written vocab reinforcement, and reduced the time we spent playing the team-based vocab/term review game I wrote for our interactive whiteboards some years ago. To a lesser extent, I also cut back on some oral reading comprehension spot-checks that accompany my whole-class reading sessions. On balance, I think Anki was a much better way to spend the time, but it's complicated. Keep reading.

这 8 分钟是 55 分钟课时的重要组成部分,特别是对于像我这样的老师来说,每分钟都要填满。必须要有所舍弃。对我来说,我完全削减了一些书面词汇的强化,并减少了我们玩我几年前为我们的交互式白板编写的基于团队的词汇/术语复习游戏的时间。在较小的程度上,我还减少了伴随全班阅读课的一些口头阅读理解抽查。总的来说,我认为 Anki 是一个更好的方式来花费时间,但这很复杂。继续阅读。

Whole-class SRS not ideal

整个班级 SRS 并不理想

Every student is different, and would get the most out of having a personal Anki profile determine when they should see each card. Also, most individuals could study many more cards per minute on their own than we averaged doing it together. (To be fair, a small handful of my students did use the software independently, judging from Ankiweb download stats)

每个学生都是不同的,由个人的 Anki 配置文件来决定他们什么时候应该看到每张卡片,会得到最大的好处。而且,大多数人每分钟自己学习的卡片比我们一起学习的平均数量多得多。公平地说,从 Ankiweb 的下载统计来看,我的一小部分学生确实在独立使用这个软件。

Getting student buy-in

获得学生的认可

Before we started using SRS I tried to sell my students on it with a heartfelt, over-prepared 20 minute presentation on how it works and the superpowers to be gained from it. It might have been a waste of time. It might have changed someone's life. Hard to say.

在我们开始使用 SRS 之前,我试着向我的学生推销它,用一个发自内心的、准备过度的、20 分钟的演示来介绍它的工作原理和从中获得的超级力量。这可能是浪费时间。它可能改变了某人的生活。这很难说。

As for the daily class review, I induced engagement partly through participation points that were part of the final semester grade, and which students knew I tracked closely. Raising a hand could earn a kind of bonus currency, but was never required—unlike looking up front and showing colors during polls, which I insisted on. When I thought students were just reflexively holding up the same color and zoning out, I would sometimes spot check them on the last card we did and penalize them if warranted.

至于每天的课堂复习,我部分是通过参与积分来诱导学生参与,这些积分是学期最终成绩的一部分,学生们知道我在密切跟踪。举手可以获得一种奖励货币,但绝不是必须的——不像我坚持的那样,在投票时要看前面并显示颜色。当我认为学生们只是反射性地举起同一种颜色,然后昏昏欲睡时,我有时会抽查他们在最后一张卡片上的表现,如果有必要的话,会对他们进行惩罚。

But because I know my students are not strongly motivated by grades, I think the most important influence was my attitude. I made it a point to really turn up the charm during review and play the part of the engaging game show host. Positive feedback. Coaxing out the lurkers. Keeping that energy up. Being ready to kill and joke about bad cards. Reminding classes how awesome they did on tests and assignments because they knew their Anki stuff.

但是,因为我知道我的学生对成绩没有强烈的动机,我认为最重要的影响是我的态度。我在复习过程中真正发挥了魅力,扮演了一个引人入胜的游戏节目主持人的角色。积极的反馈。哄骗潜水者。保持这种活力。准备好干掉和取笑烂卡片。提醒同学们他们在考试和作业中的表现有多棒,因为他们知道他们 Anki 的材料。

(This is a good time to point out that the average review time per class period stabilized at about 8 minutes because I tried to end reviews before student engagement tapered off too much, which typically started happening at around the 6-7 minute mark. Occasional short end-of-class reviews mostly account for the difference.)

(这是一个很好的时机来指出,每个课时的平均复习时间稳定在 8 分钟左右,因为我试图在学生参与度下降太多之前结束复习,通常在 6-7 分钟左右开始。偶尔的简短的课后复习主要是造成这种差异的原因。)

I also got my students more on the Anki bandwagon by showing them how this was directly linked reduced note-taking requirements. If I could trust that they would remember something through Anki alone, why waste time waiting for them to write it down? They were unlikely to study from those notes anyway. And if they aren't looking down at their paper, they'll be paying more attention to me. I better come up with more cool things to tell them!

我还让我的学生们更多地使用Anki,向他们展示这与减少记笔记的要求直接相关。如果我可以相信他们仅仅通过 Anki 就能记住一些东西,为什么还要浪费时间等他们写下来呢?反正他们也不可能根据这些笔记来学习。而且,如果他们不低头看他们的纸,他们就会更注意我。我最好能想出更多很酷的事情来告诉他们!

Making memories

制造回忆

Everything I had read about spaced repetition suggested it was a great reinforcement tool but not a good way to introduce new material. With that in mind, I tried hard to find or create memorable images, examples, mnemonics, and anecdotes that my Anki cards could become hooks for, and to get those cards into circulation as soon as possible. I even gave this method a mantra: "vivid memory, card ready".

我所读到的关于间隔重复的所有资料都表明,它是一个很好的强化工具,但不是一个介绍新材料的好方法。考虑到这一点,我努力寻找或创造令人难忘的图像、例子、记忆法和轶事,让我的 Anki 卡片能够成为钩子,并尽快让这些卡片进入流通。我甚至给了这个方法一个口号。"生动记忆,卡片准备 "。

When a student during review raised their hand, gave me a pained look, and said, "like that time when...." or "I can see that picture of..." as they struggled to remember, I knew I had done well. (And I would always wait a moment, because they would usually get it.)

当一个学生在复习时举起手,痛苦地看了我一眼,说:“就像那次……”或“我能看到……的照片”时,他们挣扎着回忆,我知道我做得很好(我总是会等一会儿,因为他们通常都会记起来。)

Baby cards need immediate love

婴儿卡片需要及时的关爱

Unfortunately, if the card wasn't introduced quickly enough—within a day or two of the lesson—the entire memory often vanished and had to be recreated, killing the momentum of our review. This happened far too often—not because I didn't write the card soon enough (I stayed really on top of that), but because it didn't always come up for study soon enough. There were a few reasons for this:

- We often had too many due cards to get through in one session, and by default Anki puts new cards behind due ones.

- By default, Anki only introduces 20 new cards in one session (I soon uncapped this).

- Some cards were in categories that I gave lower priority to.

不幸的是,如果卡片介绍得不够快——在课后一两天内——整个记忆往往就消失了,不得不重新创建,从而扼杀了我们复习的动力。这种情况发生得太频繁了——不是因为我没有尽快写出卡片(我一直很重视这个问题),而是因为它并不总是能很快出现在学习中。这有几个原因。

- 我们通常有太多的到期卡,无法在一个会话中通过,并且默认情况下 Anki 将新卡放在到期卡之后。

- 默认情况下,Anki 在一个会话中只引入 20 张新卡(我很快就取消了这个上限)。

- 有些卡片属于我优先级别较低的类别。

Two obvious cures for this problem:

- Make fewer cards. (I did get more selective as the year went on.)

- Have all cards prepped ahead of time and introduce new ones at the end of the class period they go with. (For practical reasons, not the least of which was the fact that I didn't always know what cards I was making until after the lesson, I did not do this. I might able to next year.)

解决这个问题有两个明显的方法:

- 少做卡片(随着这一年的过去,我确实变得更挑剔了。)

- 提前准备好所有卡片,并在下课时介绍新卡片(出于实际的原因,最重要的一点是,直到课后我才知道自己在做什么牌,所以我没有这样做。我明年也许可以。)

Days off suck

休息日真糟糕

SRS is meant to be used every day. When you take weekends off, you get a backlog of due cards. Not only do my students take every weekend and major holiday off (slackers), they have a few 1-2 week vacations built into the calendar. Coming back from a week's vacation means a 9-day backlog (due to the weekends bookending it). There's no good workaround for students that won't study on their own. The best I could do was run longer or multiple Anki sessions on return days to try catch up with the backlog. It wasn't enough. The "caught up" condition was not normal for most classes at most points during the year, but rather something to aspire to and occasionally applaud ourselves for reaching. Some cards spent weeks or months on the bottom of the stack. Memories died. Baby cards emerged stillborn. Learning was lost.

SRS 应该每天使用。当你周末休假的时候,你会收到一大堆到期卡片。我的学生不仅每个周末和重要的假期都休息(懒汉),他们还有一些 1-2 周的假期。从一周的假期回来意味着 9 天的积压(由于周末的预订)。对于不自学的学生来说,没有好的解决办法。我所能做的就是在返回日练习更长时间或多个 Anki 会话,试图赶上积压工作。这还不够。在这一年的大部分时间里,这种“被追赶”的状况对大多数班级来说都不正常,而是一种值得向往的东西,偶尔也会为自己的成就鼓掌。有些卡片在最底层花了数周或数月的时间。记忆消失了。婴儿卡片死产了。学习被丢失了。

Needless to say, the last weeks of the school year also had a certain silliness to them. When the class will never see the card again, it doesn't matter whether I push the button that says 11 days or the one that says 8 months. (So I reduced polling and accelerated our cards/minute rate.)

不用说,学年的最后几个星期对他们来说也有些愚蠢。当全班再也看不到卡片的时候,我按下的按钮是 11 天还是 8 个月都无关紧要(所以我减少了投票,加快了卡片/分钟的速度。)

Never before SRS did I fully appreciate the loss of learning that must happen every summer break.

在SRS之前,我从未充分认识到每年暑假必须发生的学习损失。

Triage

分诊

I kept each course's master deck divided into a few large subdecks. This was initially for organizational reasons, but I eventually started using it as a prioritizing tool. This happened after a curse-worthy discovery: if you tell Anki to review a deck made from subdecks, due cards from subdecks higher up in the stack are shown before cards from decks listed below, no matter how overdue they might be. From that point, on days when we were backlogged (most days) I would specifically review the concept/terminology subdeck for the current semester before any other subdecks, as these were my highest priority.

我把每门课的主牌组分成几个大的子牌组。这最初是出于组织上的原因,但我最终开始使用它作为一个优先排序工具。这是在一个值得诅咒的发现之后发生的:如果你让 Anki 复习一副由子牌组组成的牌组,那么在牌堆中较高的子牌组中到期的卡片将显示在下面列出的子牌组中的卡片之前,不管它们有多大的过期。从这一点上说,在我们积压的日子里(大多数日子),我会在任何其他子牌组之前,特别回顾本学期的概念/术语子牌组,因为这些是我的最高优先级。

On a couple of occasions, I also used Anki's study deck tools to create temporary decks of especially high-priority cards.

有几次,我还使用 Anki 的学习牌组工具来创建特别高优先级的临时牌组。

Seizing those moments

抓住那些时刻

Veteran teachers start acquiring a sense of when it might be a good time to go off book and teach something that isn't in the unit, and maybe not even in the curriculum. Maybe it's teaching exactly the right word to describe a vivid situation you're reading about, or maybe it's advice on what to do in a certain type of emergency that nearly happened. As the year progressed, I found myself humoring my instincts more often because of a new confidence that I can turn an impressionable moment into a strong memory and lock it down with a new Anki card. I don't even care if it will ever be on a test. This insight has me questioning a great deal of what I thought knew about organizing a curriculum. And I like it.

资深教师们开始掌握一种意识,知道什么时候可以脱离书本,教一些单元中没有的东西,甚至可能不在课程中。也许是教正确的词来描述你读到的一个生动的情况,或者是关于在某一类型的紧急情况下该怎么做的建议,这些都差点发生。随着这一年的进展,我发现自己更经常地顺应自己的直觉,因为我有一种新的自信,我可以把一个印象深刻的时刻变成一个强烈的记忆,并用一张新的Anki卡片锁定它。我甚至不关心它是否会出现在考试中。这种洞察力让我对我所认为的关于组织课程的大量知识提出质疑。而且我喜欢这样。

A lifeline for low performers

表现不佳者的生命线

An accidental discovery came from having written some cards that were, it was immediately obvious to me, much too easy. I was embarrassed to even be reading them out loud. Then I saw which hands were coming up.

一个偶然的发现来自于写了一些卡片,这对我来说很明显,太容易了。我都不好意思大声念出来。然后我看到哪只手举起来。

In any class you'll get some small number of extremely low performers who never seem to be doing anything that we're doing, and, when confronted, deny that they have any ability whatsoever. Some of the hands I was seeing were attached to these students. And you better believe I called on them.

在任何一门课上,你都会遇到少数表现极低的人,他们似乎从来没有做过我们正在做的任何事情,而且,面对面时,否认他们有任何能力。我看到的一些手依附在这些学生身上。你最好相信我拜访过他们。

It turns out that easy cards are really important because they can give wins to students who desperately need them. Knowing a 6th grade level card in a 10th grade class is no great achievement, of course, but the action takes what had been negative morale and nudges it upward. And it can trend. I can build on it. A few of these students started making Anki the thing they did in class, even if they ignored everything else. I can confidently name one student I'm sure passed my class only because of Anki. Don't get me wrong—he just barely passed. Most cards remained over his head. Anki was no miracle cure here, but it gave him and I something to work with that we didn't have when he failed my class the year before.

事实证明,简单的卡片是非常重要的,因为它们可以给那些迫切需要它们的学生带来胜利。当然,在 10 年级的班级里知道一张 6 年级水平的卡片并不是什么了不起的成就,但是这一行动会让原本消极的士气上升。它可以成为潮流。我可以在它的基础上再接再厉。一些学生开始把 Anki 当成他们在课堂上做的事情,即使他们忽略了其他的一切。我可以自信地说出一个学生的名字,我确信我通过了我的课程,仅仅是因为 Anki。别误会,他只是勉强及格。大多数牌都留在他头上。Anki 在这里并不是什么灵丹妙药,但它给了他和我一些东西,这是前年他不及格时我们所没有的。

A springboard for high achievers

成绩优异者的跳板

It's not even fair. The lowest students got something important out of Anki, but the highest achievers drank it up and used it for rocket fuel. When people ask who's widening the achievement gap, I guess I get to raise my hand now.

这甚至不公平。成绩最低的学生从 Anki 中学到了一些重要的东西,但成绩最高的学生却把这些东西喝光,用它们做火箭燃料。当人们问是谁在扩大成就差距时,我想我现在应该举手了。

I refuse to feel bad for this. Smart kids are badly underserved in American public schools thanks to policies that encourage staff to focus on that slice of students near (but not at) the bottom—the ones who might just barely be able to pass the state test, given enough attention.

我拒绝为此感到难过。在美国公立学校,聪明的孩子受到的教育严重不足,这要归功于相关政策,这些政策鼓励教职员工把注意力集中在那些接近(但不是在)底层的学生身上,而这些学生在受到足够关注的情况下,可能只能勉强通过州考试。

Where my bright students might have been used to high Bs and low As on tests, they were now breaking my scales. You could see it in the multiple choice, but it was most obvious in their writing: they were skillfully working in terminology at an unprecedented rate, and making way more attempts to use new vocabulary—attempts that were, for the most part, successful.

在我聪明的学生可能已经习惯了 B+ 和 A- 的考试,他们现在打破了我的尺度。你可以从多项选择中看到这一点,但最明显的是在他们的写作中:他们以前所未有的速度熟练地使用术语,并且更多地尝试使用新词汇,这些尝试在很大程度上是成功的。

Given the seemingly objective nature of Anki it might seem counterintuitive that the benefits would be more obvious in writing than in multiple choice, but it actually makes sense when I consider that even without SRS these students probably would have known the terms and the vocab well enough to get multiple choice questions right, but might have lacked the confidence to use them on their own initiative. Anki gave them that extra confidence.

鉴于 Anki 看似客观的性质,写作的好处可能比选择题更明显,这似乎违反直觉,但当我考虑到即使没有 SRS,这些学生可能已经足够了解术语和词汇,从而正确回答选择题时,这实际上是有道理的,但他们可能缺乏主动使用它们的信心。Anki 给了他们额外的信心

A wash for the apathetic middle?

为冷漠的中间派洗白?

I'm confident that about a third of my students got very little out of our Anki review. They were either really good at faking involvement while they zoned out, or didn't even try to pretend and just took the hit to their participation grade day after day, no matter what I did or who I contacted.

我相信,大约三分之一的学生从我们的 Anki 复习中得到的很少。他们要么真的很擅长在分心的时候假装参与,要么甚至不假装,只是日复一日地把打击带到参与年级,不管我做了什么,也不管我联系了谁。

These weren't even necessarily failing students—just the apathetic middle that's smart enough to remember some fraction of what they hear and regurgitate some fraction of that at the appropriate times. Review of any kind holds no interest for them. It's a rerun. They don't really know the material, but they tell themselves that they do, and they don't care if they're wrong.

这些学生甚至不一定是不及格的,他们只是一个冷漠的中间派,他们足够聪明,能够记住他们听到的部分内容,并在适当的时候反刍其中的部分内容。他们对任何形式的复习都不感兴趣。这是重播。他们不知道材料,但他们告诉自己他们知道,他们不在乎自己是否错了。

On the one hand, these students are no worse off with Anki than they would have been with with the activities it replaced, and nobody cries when average kids get average grades. On the other hand, I'm not ok with this... but so far I don't like any of my ideas for what to do about it.

一方面,这些学生在 Anki 上的表现并不比在 Anki 所取代的活动上差,当普通孩子的成绩达到平均水平时,没有人会哭泣。另一方面,我不同意。。。但到目前为止,我不喜欢我的任何想法做什么。

Putting up numbers: a case study

提出数字:一个案例研究

For unplanned reasons, I taught a unit at the start of a quarter that I didn't formally test them on until the end of said quarter. Historically, this would have been a disaster. In this case, it worked out well. For five weeks, Anki was the only ongoing exposure they were getting to that unit, but it proved to be enough. Because I had given the same test as a pre-test early in the unit, I have some numbers to back it up. The test was all multiple choice, with two sections: the first was on general terminology and concepts related to the unit. The second was a much harder reading comprehension section.

由于计划外的原因,我在一个季度开始时教了一个单元,直到该季度结束时才正式测试他们。从历史上看,这将是一场灾难。但在这种情况下,它的效果却很好。五个星期以来,Anki 是他们接触该单元的唯一机会,但事实证明这已经足够了。因为我在该单元的早期进行了同样的测试,所以我有一些数据支持。测试全部是选择题,有两个部分:第一部分是与该单元有关的一般术语和概念。第二部分是难度更大的阅读理解。

As expected, scores did not go up much on the reading comprehension section. Overall reading levels are very difficult to boost in the short term and I would not expect any one unit or quarter to make a significant difference. The average score there rose by 4 percentage points, from 48 to 52%.

正如所料,阅读理解部分的分数并没有上升多少。总体阅读水平很难在短期内提高,我不认为任何一个单元或季度会产生重大影响。平均得分上升了 4 个百分点,从 48% 上升到 52%。

Scores in the terminology and concept section were more encouraging. For material we had not covered until after the pre-test, the average score rose by 22 percentage points, from 53 to 75%. No surprise there either, though; it's hard to say how much credit we should give to SRS for that.

术语和概念部分的分数更令人鼓舞。对于我们在预测试之后才涉及到的材料,平均得分上升了 22 个百分点,从 53% 上升到 75%。不过,这也不奇怪;很难说我们应该归功于 SRS 多少。

But there were also a number of questions about material we had already covered before the pretest. Being the earliest material, I might have expected some degradation in performance on the second test. Instead, the already strong average score in that section rose by an additional 3 percentage points, from 82 to 85%. (These numbers are less reliable because of the smaller number of questions, but they tell me Anki at least "locked in" the older knowledge, and may have strengthened it.)

但也有一些问题是关于我们在预测试之前已经讨论过的材料。作为最早的材料,我可能预料到第二次测试的表现会有所下降。取而代之的是,这一部分本来就强劲的平均分又上升了 3 个百分点,从 82% 上升到 85%(这些数字不太可靠,因为问题的数量较少,但它们告诉我,Anki 至少“锁定”了旧知识,并可能加强了它。)

Some other time, I might try reserving a section of content that I teach before the pre-test but don't make any Anki cards for. This would give me a way to compare Anki to an alternative review exercise.

另外一些时候,我可能会尝试保留一节我在考前教的内容,但不做任何 Anki 卡片。这将使我有办法将 Anki 与另一种复习练习进行比较。

What about formal standardized tests?

那正式的标准化考试呢?

I don't know yet. The scores aren't back. I'll probably be shown some "value added" analysis numbers at some point that tell me whether my students beat expectations, but I don't know how much that will tell me. My students were consistently beating expectations before Anki, and the state gave an entirely different test this year because of legislative changes. I'll go back and revise this paragraph if I learn anything useful.

我还不知道。分数还没有回来。我可能会在某个时候看到一些 "增值" 分析数字,告诉我我的学生是否超过了预期,但我不知道这能告诉我多少。在 Anki 之前,我的学生一直都能超越预期,而今年由于立法的变化,州政府给出了一个完全不同的测试。如果我学到什么有用的东西,我会回去修改这一段。

Those discussions...

那些讨论。。。

If I'm trying to acquire a new skill, one of the first things I try to do is listen to skilled practitioners of that skill talk about it to each other. What are the terms-of-art? How do they use them? What does this tell me about how they see their craft? Their shorthand is a treasure trove of crystallized concepts; once I can use it the same way they do, I find I'm working at a level of abstraction much closer to theirs.

如果我想掌握一项新的技能,我首先要做的事情是听该技能的熟练从业者对彼此谈论它。艺术术语是什么?他们是如何使用这些术语的?这告诉我他们如何看待自己的技艺?他们的速记是一个结晶概念的宝库;一旦我能够像他们那样使用它,我就会发现我在一个更接近他们的抽象层次上工作。

Similarly, I was hoping Anki could help make my students more fluent in the subject-specific lexicon that helps you score well in analytical essays. After introducing a new term and making the Anki card for it, I made extra efforts to use it conversationally. I used to shy away from that because so many students would have forgotten it immediately and tuned me out for not making any sense. Not this year. Once we'd seen the card, I used the term freely, with only the occasional reminder of what it meant. I started using multiple terms in the same sentence. I started talking about writing and analysis the way my fellow experts do, and so invited them into that world.

同样地,我希望 Anki 能够帮助我的学生更流畅地使用特定学科的词汇,以帮助你在分析性文章中取得好成绩。在介绍了一个新术语并制作了 Anki 卡片之后,我更加努力地在对话中使用它。我曾经对这种做法感到羞愧,因为许多学生会立即忘记它,并因为我没有任何意义而把我调开。今年则不然。一旦我们看到这张卡片,我就自由地使用这个术语,只是偶尔提醒一下它的含义。我开始在同一个句子中使用多个术语。我开始像我的专家同伴那样谈论写作和分析,因此邀请他们进入那个世界。

Even though I was already seeing written evidence that some of my high performers had assimilated the lexicon, the high quality discussions of these same students caught me off guard. You see, I usually dread whole-class discussions with non-honors classes because good comments are so rare that I end up dejectedly spouting all the insights I had hoped they could find. But by the end of the year, my students had stepped up.

尽管我已经看到书面证据表明我的一些成绩好的学生已经吸收了这些词汇,但这些学生的高质量讨论让我措手不及。你看,我通常害怕非荣誉班的全班讨论,因为好的评论是如此罕见,以至于我最后垂头丧气地吐出了我希望他们能找到的所有见解。但是到了年底,我的学生们都站了出来。

I think what happened here was, as with the writing, as much a boost in confidence as a boost in fluency. Whatever it was, they got into some good discussions where they used the terminology and built on it to say smarter stuff.

我认为这里发生的事情和写作一样,既是对信心的提升,也是对流畅性的提升。不管是什么,他们进行了一些很好的讨论,他们使用术语并在此基础上说出更聪明的东西。

Don't get me wrong. Most of my students never got to that point. But on average even small groups without smart kids had a noticeably higher level of discourse than I am used to hearing when I break up the class for smaller discussions.

别误会我。我的大多数学生都没有达到这一点。但平均而言,即使是没有聪明孩子的小组,其论述水平也明显高于我所习惯的将班级分开进行小型讨论时听到的水平。

Limitations

局限性

SRS is inherently weak when it comes to the abstract and complex. No card I've devised enables a student to develop a distinctive authorial voice, or write essay openings that reveal just enough to make the reader curious. Yes, you can make cards about strategies for this sort of thing, but these were consistently my worst cards—the overly difficult "leeches" that I eventually suspended from my decks.

当涉及到抽象和复杂的问题时,SRS 本身就很弱。我设计的卡片中没有一张能让学生发展出独特的作者风格,也没有一张能让读者好奇的文章开头。是的,你可以制作关于这类事情的策略的卡片,但是这些卡片一直是我最糟糕的卡片——我最终从我的牌组中暂停的过于困难的“水蛭”。

A less obvious limitation of SRS is that students with a very strong grasp of a concept often fail to apply that knowledge in more authentic situations. For instance, they may know perfectly well the difference between "there", "their", and "they're", but never pause to think carefully about whether they're using the right one in a sentence. I am very open to suggestions about how I might train my students' autonomous "System 1" brains to have "interrupts" for that sort of thing... or even just a reflex to go back and check after finishing a draft.

SRS 的一个不太明显的局限性是,对一个概念有很强理解力的学生往往无法在更真实的情境中应用这些知识。例如,他们可能非常清楚“there”、“their”和“they's”之间的区别,但从不停下来仔细考虑自己在句子中是否使用了正确的词。我非常愿意接受关于如何训练我的学生的自主“系统1”的大脑,使之对这类事情有“中断”的建议。。。或者仅仅是一个反射,在完成一个草稿后,回去检查。

Moving forward

前进

I absolutely intend to continue using SRS in the classroom. Here's what I intend to do differently this coming school year:

我绝对打算继续在教室里使用 SRS。以下是我打算在下一学年采取的不同做法:

- Reduce the number of cards by about 20%, to maybe 850-950 for the year in a given course, mostly by reducing the number of variations on some overexposed concepts.

- 减少卡片数量大约 20%,在一个给定的课程中,一年内可能会减少 850-950 张,主要是通过减少一些过度曝光的概念的变化数量。

- Be more willing to add extra Anki study sessions to stay better caught-up with the deck, even if this means my lesson content doesn't line up with class periods as neatly.

- 更愿意增加额外的 Anki 学习会话,以更好地赶上这套牌组,即使这意味着我的课程内容与上课时间不一致。

- Be more willing to press the red button on cards we need to re-learn. I think I was too hesitant here because we were rarely caught up as it was.

- 更愿意对我们需要重新学习的卡片按下红色按钮。我想我在这里太犹豫了,因为我们很少能像现在这样。

- Rework underperforming cards to be simpler and more fun.

- 重做表现不佳的卡片使其更简单、更有趣。

- Use more simple cloze deletion cards. I only had a few of these, but they worked better than I expected for structured idea sets like, "characteristics of a tragic hero".

- 使用更简单的填空卡片。我只有几张这样的卡片,但对于结构化的想法集,如 "悲剧英雄的特征",它们比我预期的效果要好。

- Take a less linear and more opportunistic approach to introducing terms and concepts.

- 采用一种不那么线性、更机会主义的方法来引入术语和概念。

- Allow for more impromptu discussions where we bring up older concepts in relevant situations and build on them.

- 允许更多的即兴讨论,我们在相关情况下提出旧的概念,并在此基础上进行讨论。

- Shape more of my lessons around the "vivid memory, card ready" philosophy.

- 我的课程更多的是围绕着“生动记忆,卡片准备”哲学。

- Continue to reduce needless student note-taking.

- 继续减少学生不必要的记笔记。

- Keep a close eye on 10th grade students who had me for 9th grade last year. I wonder how much they retained over the summer, and I can't wait to see what a second year of SRS will do for them.

- 密切关注去年在我这里上九年级的十年级学生。我不知道他们在暑假期间保留了多少东西,我迫不及待地想看看第二年的 SRS 会对他们产生什么影响。

Suggestions and comments very welcome!

欢迎提出建议和意见!