本文使用 Zhihu On VSCode 创作并发布

Description

说明

This is a reflective essay and report on my experiences using Spaced Repetition Software (SRS) in an American high school classroom. It follows my 2015 and 2016 posts on the same topic.

这是一篇关于我在美国高中课堂上使用间隔重复软件(SRS)经验的反思性文章和报告。它是继我 2015 和 2016 关于同一主题的帖子之后的又一篇文章。

Because I value concise summaries in non-fiction, I provide one immediately below. However, I also believe in the power of narrative, in carefully unfolding a story so as to maximize reader engagement and impact. As I have applied such narrative considerations in writing this post, I consider the following summary to be a spoiler.

因为我重视非小说的简明摘要,所以我在下面立即提供了一个。然而,我也相信叙事的力量,相信谨慎地展开一个故事,能以最大限度地提高读者的参与度和影响力。由于我在写这篇文章时运用了这样的叙事考虑,我认为下面的摘要是一个剧透。

I’ll let you decide what to do with that information.

我让你决定怎么处理这些信息。

Summary (spoilers)

摘要(剧透)

My earlier push for classroom SRS solutions was driven by a belief I came to see as fallacious: that forgetting is the undoing of learning. This epistemic shift drove me to abandon designs for a custom app that would have integrated whole-class and individual SRS functions.

我早先推动课堂 SRS 解决方案的动力来自于一个我现在认为是谬误的信念:遗忘是学习的撤销。这种认识上的转变促使我放弃了对一个定制应用程序的设计,该应用程序将整合整个班级和个人的 SRS 功能。

While I still see value in classroom use of Spaced Repetition Software, especially in basic language acquisition, I have greatly reduced its use in my own classes.

虽然我仍然看到在课堂上使用间隔重复软件的价值,特别是在基础语言习得方面,但我已经大大减少了在我自己的课堂上使用间隔重复软件。

In my third year of experiments (2016-17), I used a windfall of classroom computers to give students supervised time to independently study using an SRS app with individual profiles. I found longer-term average performance to be slightly worse than under the whole-class group study model, though students of high intelligence and motivation saw slight improvements.

在我第三年的实验中(2016-17年),我利用教室里大量的电脑,让学生在监督下使用带有个人档案的 SRS 应用程序独立学习。我发现长期的平均成绩比全班集体学习模式下的成绩略差,不过高智商和高积极性的学生的成绩略有提高。

Intro and response to Piotr Woźniak

介绍与回应 Piotr Woźniak

I have recently received a number of requests to revisit the topic of classroom SRS after years of silence on the subject. Understandably, the term “postmortem” has come up more than once. Did I hit a dead end? Do I still use it?

我最近收到了一些请求,希望我在多年来对这个问题保持沉默之后,重新讨论课堂 SRS 这个话题。可以理解的是,"事后总结"这个词不止一次出现。我是不是走到了死胡同?我还在使用它吗?

Also, I was informed that SRS founding father Piotr Woźniak recently added a page to his SuperMemo wiki in which he quoted me at length and claimed that SRS doesn’t belong in the classroom.

另外,我被告知,SRS 的创始人 Piotr Woźniak 最近在他的 SuperMemo wiki 上添加了一页,他在其中详细地引用了我的话,并声称 SRS 不属于课堂。

Well, I don’t have much in the way of rebuttal, because Woźniak’s main goal with the page seems to be to use my experience as ammunition against the perpetuation of school-as-we-know-it, which seems like a worthy crusade. He introduces my earlier classroom SRS posts by saying, “This teacher could write the same articles with the same conclusions. Only the terminology would differ.” I’ll take that as high praise.

好吧,我没有太多的反驳,因为 Woźniak 在这个页面上的主要目标似乎是利用我的经验作为弹药,反对我们所知道的学校的永久化,这似乎是一个值得的讨伐。他在介绍我早期的课堂 SRS 帖子时说:"这位老师可以写出同样的文章,得出同样的结论。只有术语会有所不同"。我认为这是对我的高度赞扬。

If I were to quibble, it would be with the part shortly after this, where he says:

The entire analysis is made with an important assumption: "school is good, school is inevitable, and school is here to stay, so we better learn to live with it".

如果我要吹毛求疵的话,那就是在这之后不久,他说的那段话:

整个分析是在一个重要的假设下进行的。"学校是好的,学校是不可避免的,而且学校将继续存在,所以我们最好学会与它共存 "。

Inevitable? Maybe. Here to stay? Realistically, yes. But good? At best, I might describe our educational system as an “inadequate equilibrium”. At worst? A pit so deep we still don’t know what’s at the bottom, except that it eats souls.

不可避免的?也许吧。继续存在?现实地讲,是的。但是好吗?在最好的情况下,我可以把我们的教育系统描述为"不充分的平衡"。在最坏的情况下?一个深不见底的坑,我们仍然不知道坑底是什么,只知道它吃人的灵魂。

Other than that, let me reiterate my long-running agreement with Woźniak that SRS is best when used by a self-motivated individual, and that my classroom antics are an ugly hack around the fact that self-motivation is a rare element this deep in the mines.

除此之外,让我重申我与 Woźniak 的长期共识,即 SRS 在由自我激励的个人使用时是最好的,而我在课堂上的滑稽行为是一个丑陋的篡改,它围绕着这一事实——自我激励是矿区深处的稀有元素。

Anyone who can show us a way out will have my attention. In the meantime, I’ll do my best to keep a light on.

任何能给我们指出出路的人都会引起我的注意。同时,我会尽我所能让灯亮着。

Prologue

序言

At the end of my 2016 post, I teased a peek at a classroom SRS+ app I was preparing to build. It would have married whole-class and individual study functions with some other clever features to reduce teacher workload.

在 2016 年的文章末尾,我预告了我准备建立的一个课堂 SRS+ 应用程序的情况。它将整个班级和个人学习功能与其他一些巧妙的功能结合起来,以减少教师的工作量。

I had a 10k word document in hand: a mix of rationale, feature descriptions, and hypothetical “user stories”. I wasn’t looking for funding or a co-founder, just some technical suggestions and moral support. I would have been my own first user, and I had to keep my day job for that anyway.

我手里有一份 1 万字的文档:包含了基本原理、功能描述和假设的"用户故事"。我不是在寻找资金或联合创始人,只是一些技术建议和精神支持。我本来是我自己的第一个用户,反正我必须记录我的日常工作。

But each time I read my draft, I had this growing, sickening sense that I was lying to myself and my potential customers, like a door-to-door missionary choking back a tide of latent atheism. And I should know, because the last time I had felt this kind of queasiness I was a door-to-door missionary choking back a tide of latent atheism.

但每次我读我的草稿时,我都有一种越来越强烈的、令人作呕的感觉,我在对自己和我的潜在客户撒谎,就像一个挨家挨户的传教士在扼制潜在的无神论浪潮。我应该知道,因为上一次我感到这种恶心的时候,我就是一个挨家挨户的传教士,扼杀了潜在的无神论浪潮。

I thought maybe this was just the kind of general self-doubt common to anyone undertaking something audacious, but I paused my work on it for another school year while I tried the obvious thing: providing students individual SRS app profiles and supervised class time in which to use them.

我想也许这只是任何人在做一些大胆的事情时常见的那种普遍的自我怀疑,但我在另一个学年暂停了我的工作,同时我尝试了显而易见的事情:为学生提供单独的 SRS 应用程序配置文件并监督学生在课堂时间来使用它们。

This is a two-part essay, and in Part 2, I’ll tell you how that went. But in Part 1, I’m going to make the case that Part 2 doesn’t matter very much.

这是一篇由两部分组成的文章,在第二部分中,我会告诉你这是怎么回事。但在第一部分,我将提出第二部分并不十分重要的理由。

Part 1: Everybody Poops

第一部分:每个人都会大便

A great and terrible vision

伟大而可怕的景象

As I wrapped up my Third Year experiment, I again tried to sort out my feelings about my visionary SRS app design, which I hadn’t updated despite a year of fresh experience. Was it just self-doubt?

当我结束第三年的实验时,我再次试图理清我对我那富有远见的 SRS 应用设计的感受,尽管有了一年的新鲜经验,但我还没有更新。这只是自我怀疑吗?

The fact that I could only code at a minimal hobbyist level didn’t feel like the biggest hurdle. I think I could have picked up enough skill in that area. But even with a magical ability to translate my vision into code, I would have been up against a daunting base rate of failure for education startups. Also, I didn’t consider myself a very typical teacher: What sounded brilliant and intuitive to me would probably seem pointless and nonsensical to 95% of my peers.

事实上,我只能在最低限度的业余水平上写代码,这并不是最大的障碍。我想我可以在这个领域掌握足够的技能。但是,即使有一种神奇的能力将我的设想转化为代码,我也会遇到教育创业公司令人生畏的基础失败率。此外,我不认为自己是一个非常典型的教师。对我来说,听起来很聪明、很直观的东西,在我 95% 的同行看来可能是毫无意义和荒谬的。

Still, I pulled out my Eye of Agamotto and checked out all of the futures where I developed the app. In almost all of these, nothing came of it. But in the few where my app saw high adoption, the result was… dystopia! Students turned against their teachers, and teachers against their students. Homework stretched to eternity. Millions of children cursed my name. The ‘me’ in these futures wore an ignominious goatee and a haunted stare.

尽管如此,我还是掏出了我的阿加莫托之眼,查看了我开发应用程序的所有未来。在几乎所有的未来中,都没有任何结果。但在少数几个我的应用程序被高度采用的地方,结果是......歇斯底里!学生反对他们的老师,而老师反对他们的学生。家庭作业被延长到永远。数百万的孩子诅咒我的名字。这些未来中的 "我" 留着可耻的山羊胡子,目光呆滞。

Used judiciously for the right concepts, in the right courses, by the right teachers, I still think my imagined app could be a powerful tool. But I don’t see any way to keep it from being abused. Well-intentioned teachers would put too much into it and demand too much from students. Any safeguards I put in to prevent this would just invite my app to be outcompeted by an imitator who removed these safeguards (which would seem arbitrary and restricting to most users).

在正确的课程中,由正确的老师审慎地使用正确的概念,我仍然认为我想象中的应用程序可以成为一个强大的工具。但我不认为有任何方法可以防止它被滥用。好心的老师会在其中投入太多,对学生要求太多。我为防止这种情况而设置的任何保障措施,都会使我的应用程序被取消这些保障措施的模仿者所超越(对大多数用户来说,这似乎是武断和限制性的)。

I’m convinced of this because the me who wrote the original “A Year of Spaced Repetition…” post would have abused it. Let’s see... He was averaging seven new cards a day? (That’s 2-3 times what I would recommend today.) He uncapped the 20 new card/day limit? He knew even then that he was adding too many cards, but failed to cut back the following year? I’m not encouraged.

我对此深信不疑,因为当初写《间隔重复的一年......》一文的我,会滥用它。让我们来看看... 他平均每天有七张新卡片?(这是我今天建议的 2-3 倍。)他解除了每天 20 张新卡片安排的限制?他甚至在那时就知道他增加了太多的卡片,但在第二年没有减少?我并不感到鼓舞。

“But wait,” you say. “You didn’t think you were a typical teacher. Maybe a typical teacher could be trusted?”

“等等,”你说你认为你不是一个典型的老师。也许一个典型的老师可以信任?”

No.

不。

In defense of forgetting

为了防止遗忘

The “problem” is that teachers instinctively introduce far more content than students can be expected to remember. This was obvious to me when I was averaging seven new cards a day, which still felt like a brutal triage of my total content.

"问题"在于,教师本能地介绍的内容远远多于学生预期能记住的内容。这对我来说是显而易见的,当时我平均每天要做七张新卡片,这仍然感觉是对我的总内容进行了残酷的分流。

Covering more material than can be retained isn’t bad teaching, though. In fact, it’s a good and necessary practice. Content — the more the merrier — is the training data the brain uses to form and refine mental models of the universe. These models tend to be long-lived, and allow the brain to re-learn the content more deeply and efficiently if it ever comes up again. They also allow it to absorb new-but-conceptually-adjacent contents more readily. In cognition, as in nutrition, you are what you eat — and good digestion naturally produces solid waste. The original training data is subject to lossy compression, with only a few random fragments left whole and unforgotten. (Tippecanoe, and Tyler Too! The mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell!) Such recollections are corn kernels bobbing top-side up in a turd floating down the river Lethe.

不过,涵盖超过可以记住的材料并不是糟糕的教学方法。事实上,这是一种良好的、必要的做法。内容越多越好,是大脑用来形成和完善宇宙心理模型的训练数据。这些模型往往很长寿,如果内容再次出现,可以让大脑更深入和有效地重新学习。它们还能让它更容易地吸收新的但在概念上相近的内容。在认知方面,就像在营养方面一样,你就是你所吃的东西——良好的消化自然会产生固体废物。原始训练数据要进行有损压缩,只有一些随机的片段被完整地保留下来,不被遗忘。(Tippecanoe 和 Tyler Too!线粒体是细胞的动力源!)这样的回忆是在顺着 Lethe 河漂流的粪便中上下晃动的玉米粒。

This is normal and fine. Regular, even.

这很正常,也很好。甚至是常规的。

But the educational establishment doesn’t see it that way. The teacher I was seven years ago didn’t see it that way. And I now realize that the teacher I was five and six years ago had queasy feelings because he was starting to see it that way. Following my gut, without fully understanding or even entirely registering what I was doing, I slowly turned around and started walking the other way, abandoning my app design and the unfinished “Third Year” report.

但教育机构并不这么看。七年前的我并不这么看。而我现在意识到,五年和六年前的那个老师之所以感到恶心,是因为他开始这么看了。顺着我的直觉,在没有完全理解甚至完全记住我在做什么的情况下,我慢慢地转过身来,开始走另一条路,放弃了我的应用程序设计和未完成的 "第三年"报告。

The orthodox view equates forgetting with failure. It’s not “Everybody poops”. It’s “Poop is inadequate. How can we get more corn, less poop?” This belief is implicit whenever someone laments the “summer slide” , or opines that students missing school during the Covid pandemic are “losing” months of learning — as if kids are spinning their progress meters backwards, just pooping away without anyone trying to stop them. Under this view, we keep kids in school partly to stop the leaks, and partly to stuff them with new knowledge faster than they can expunge old knowledge.

正统的观点将遗忘等同于失败。这不是 "每个人都会大便"。而是 "大便不足"。我们如何才能得到更多的玉米,更少的大便?" 每当某人感叹 "夏季滑坡",或认为在 Covid 大流行期间缺课的学生 "失去" 了几个月的学习时,就隐含着这种信念——仿佛孩子们的进度表在向后转,只是在没有人试图阻止他们的情况下大便。在这种观点下,我们让孩子们留在学校,部分是为了阻止他们排泄,部分是为了让他们以更快的速度掌握新知识,而不是清除旧知识。

If this is how you see education, SRS is a tool to keep students from pooping. It offers the tantalizing possibility of learning without forgetting. Two steps forward, no steps back. Why wouldn’t you push it as hard as possible?

如果这就是你对教育的看法,那么 SRS 就是一种防止学生大便的工具。它提供了一种诱人的可能性——学习而不遗忘。前进两步,不退一步。你为什么不尽可能地推动它呢?

Don’t get me wrong. All else being equal, learning without forgetting would be great. But the most important effects of learning — lasting changes to our mental machinery — happen whether or not we forget the content. Once the lesson is over, dear teacher, your best shot at lasting growth has already left the harbor. So why are you still trying to hold back the tide? Why are you planning to punish your students for pooping on Tuesday, the day before your test, instead of Thursday, the day after it?

别误会我。在其他条件相同的情况下,学习而不遗忘将是一件好事。但是,无论我们是否忘记内容,学习最重要的效果——对我们心理机制的持久改变——都会发生。亲爱的老师,一旦课程结束,你实现持久增长的最佳机会就已经离开了港口。那么,你为什么还在试图阻止潮水?为什么你打算在考试前一天的星期二惩罚你的学生大便,而不是在考试后一天的星期四?

In defense of remembering

为了捍卫记忆

This is not a “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Forgetting” essay. I don’t love forgetting. I will be the first to argue the merits of not forgetting right away. The longer we can keep ideas floating around in our heads, the greater their “cross-section”, as I put it in 2016, with more opportunities to make associative connections that cause useful long-lived updates to our mental models.

这不是一篇 "我如何学会停止忧虑并爱上遗忘" 的文章。我不喜欢遗忘。我将是第一个论证不马上忘记的好处的人。我们能让想法在脑海中漂浮的时间越长,它们的 "横截面" 就越大,正如我在 2016 年所说的那样,有更多机会建立联想联系,从而对我们的心智模型进行长期有效的更新。

Unfortunately, I have not found SRS to be great at fostering the sorts of reflective mental states conducive to insight, except when studying on my own at a deliberately slow pace, as while on a walk. In such a use case, SRS no longer has quite the time-efficiency advantage that is its main selling point. The opportunity cost of using it goes up. In a whole-class SRS session, long reflective pauses between cards would invite frustration and misbehavior, and we wouldn’t get through very many cards.

不幸的是,我发现 SRS 在培养有利于洞察力的那种反思性思维状态方面并不出色,除非是在我自己以刻意缓慢的速度学习的时候,比如在散步的时候。在这样的使用情况下,SRS 不再具有作为其主要卖点的时间效率优势了。使用它的机会成本上升了。在全班的 SRS 课程中,卡片之间长时间的反思停顿会招致挫败感和行为不当,而且我们也不会完成很多卡片的学习。

In defense of remembering, I will also argue that some skills are simply impossible without a continuous retention of specific dependencies. These skills tend to be technical. Heck, this might be the definition of a technical skill.

为了捍卫记忆,我还会认为,如果没有持续保留特定的依赖关系,有些技能根本不可能实现。这些技能往往是技术性的。见鬼,这可能就是技术性技能的定义。

With a few mostly upper-level exceptions, though — math, physics, chemistry — most of what we teach in school is more conceptual than technical. We make you take history so you have a better model of how civilizations and governments work, not so you remember who shot Alexander Hamilton. We make you take English to improve your word-based input and output abilities, not so you remember the difference between simile and metaphor. At least, I hope we do.

不过,除了少数高水平的例外——数学、物理、化学——我们在学校教的大多数东西都是概念性的而不是技术性的。我们让你学习历史是为了让你对文明和政府如何运作有一个更好的模型,而不是为了让你记住谁枪杀了亚历山大-汉密尔顿。我们让你学英语是为了提高你基于文字的输入和输出能力,而不是为了让你记住 "模仿"和 "隐喻" 的区别。至少,我希望我们这样做。

Besides, even in the technical classes, forgetting is the near-universal outcome, and the long-term benefits are mostly conceptual — for if you don’t use these skills continuously for the rest of your life, you’re almost certainly going to lose them. Maybe more than once.

此外,即使在技术课上,遗忘也是近乎普遍的结果,而长期的好处主要是概念性的——因为如果你不在你的余生持续使用这些技能,你几乎肯定会失去它们。也许不止一次。

I’ve forgotten algebra twice. I’ve forgotten how to write code at least three times. I can’t do either one at the moment. But I’m still changed by having known them. I have an intuition for what sorts of problems ought to be mathematically solvable. I can think in terms of algorithms. And I could relearn either skill more easily than on the first or second occasions. Also, relearning has an anecdotal tendency to deepen understanding in a way that continuous retention may not, especially when approached from a different direction.

我已经忘记了两次代数。我已经忘记了如何写代码至少三次了。目前这两件事我都不会做。但我还是因为了解它们而改变了。我对什么样的问题在数学上是可以解决的有一种直觉。我可以用算法的方式思考问题。而且我可以比第一次或第二次更容易地重新学习这两种技能。另外,重新学习传闻有一种加深理解的倾向,而持续保留可能不会,特别是当从不同的方向接近时。

Still, as long as I’m defending retention, I think it’s valid to ask whether we should force kids (and often, by extension, their parents) to relearn math every frickin’ year. Consider: The conventional wisdom is that technical companies begrudgingly expect to have to (re)train most new workers in the very specific areas they need. They look to your resume and transcripts mostly for evidence that you have learned technical skills before and can presumably learn them again. I don’t think they care if you’ve re-learned them three times already instead of six. So, if we’re going to force kids to demonstrate intermediate math chops to graduate (a dubious demand), perhaps we could at least wait until the last practical moment, and then do it in bigger continuous lumps — like two-hour daily block classes starting in grade 9 or 10 — so they would have fewer opportunities to forget as they climb the dependency pyramid. Think of the tears we could save (or at least postpone).

不过,只要我在为保留率辩护,我认为我们有必要问一问,我们是否应该强迫孩子(通常也包括他们的父母)每年重新学习数学。想想看:传统的观点是,技术公司勉强地期望在他们所需要的非常具体的领域中对大多数新工人进行(重新)培训。他们看你的简历和成绩单,主要是为了证明你以前学过技术技能,而且可能会再次学习这些技能。我认为他们并不关心你是否已经重新学习了三次而不是六次。因此,如果我们要强迫孩子们展示中级数学能力才能毕业(这是一个可疑的要求),也许我们至少可以等到最后的实际时刻,然后以更大的连续块状方式进行——比如从九年级或十年级开始每天两小时的块状课程——这样他们在攀登依赖金字塔时就会有更少机会忘记。想想我们可以节省多少眼泪(或至少推迟)。

The value proposition of classroom SRS

课堂 SRS 的价值主张

Anyway, classroom SRS has its strengths, but midwifing conceptual insights doesn’t feel like one of them. I think it’s also reasonable to assume that students forget almost everything from a classroom SRS deck as soon as they stop using it.

总之,课堂 SRS 有它的优势,但培养概念性的见解感觉不是其中之一。我认为有理由认为,学生一旦停止使用课堂 SRS 牌组,就会忘记它的几乎所有内容。

Adjusting for these two assumptions, the terrain where classroom SRS can beat out its opportunity costs dramatically shrinks. But I believe it still exists, at the intersection of high automaticity targets and medium-term objectives.

对这两个假设进行调整后,课堂 SRS 能够战胜其机会成本的领域就会急剧缩小。但我相信它仍然存在,在高自动性目标和中期目标的交叉点上。

With high automaticity targets, what you’re trying to train is a reflexive response to a stimulus that is going to look a lot like the study card. Foreign language vocabulary is my poster child for this. You’re not drilling the words to unearth insights. You’re drilling for speed, so that they can keep up when a word pops up in a real-time conversation.

对于高自动性目标,你要训练的是对刺激物的反射性反应,而这种刺激物看起来很像学习卡片。外语词汇是我在这方面的典型例子。你钻研这些单词并不是为了发掘洞察力。你是在训练速度,这样他们就能在实时对话中出现一个词时跟上。

You’re also trying to drill away the need for conscious awareness. You want that front-side combination of sounds or letters to cause the back-side set of sounds or letters to pop automatically into their heads. This is my intent when I drill my English students in word fragments (prefixes, roots, suffixes), which are really just bits of foreign language (Greek, Latin). If it’s not automatic, then they’ll gloss right over the possible meaning of “salubrious”, even though they have learned that “salu” usually means “health”.

你也在努力钻研,以消除对意识的需求。你想让前面的声音或字母组合导致后面的声音或字母组合自动出现在他们的头脑中。这就是我给我的英语学生操练单词片段(前缀、词根、后缀)时的意图,这实际上只是外语(希腊语、拉丁语)的片段。如果不是自动的,那么他们就会直接忽略 "salubrious" 的可能含义,尽管他们已经知道 "salu" 通常意味着 "健康"。

By medium-term objective, I mean “I want my students to have automatic fluency with the content of these cards on Day X”, where X is a date between one week and three months in the future. It shouldn’t be sooner than that, in accordance with Gwern’s “5 and 5” rule: You probably need at least five days to get any real advantage from SRS. And it shouldn’t be later than a few months, for two reasons: First, we’re assuming the students will forget it all once they stop studying, which is all but guaranteed after the end of the course; there’s little point in keeping those cards in rotation after Day X. Second, I probably don’t want to start those cards until the last practical minute, which is unlikely to be more than three months ahead of time.

我所说的中期目标是指 "我希望我的学生在第X天自动流畅地掌握这些卡片的内容",其中X是未来一周到三个月之间的一个日期。根据格温的 "5 和 5"规则,它不应该比这更早。你可能至少需要五天才能从 SRS 中获得任何真正的好处。而且它不应该长于几个月,原因有二。首先,我们假设学生一旦停止学习就会忘记这一切,这在课程结束后是可以保证的;在第X天之后保持这些卡片的轮流使用没有什么意义。其次,我可能不想在最后的实际时刻才开始使用这些卡片,这不太可能提前超过三个月。

Why three months and not six? It’s not a hard-and-fast rule, but from the experience of my first three years of classroom SRS, if you’re trying to retain things for more than a few months, the total number of cards is likely to become greater than you can productively study every day, and many cards will languish unseen. Plus, your roster can change, especially over a semester break. The set of students you have in six months might only have 70% overlap with the set you have now. Really, you should wait until the last practical minute.

为什么是三个月而不是六个月?这不是一条硬性规定,但根据我前三年课堂 SRS 的经验,如果你想保留的东西超过几个月,卡片的总数很可能会超过你每天可以有效学习的数量,许多卡片会被搁置起来,不被人看到。另外,你的名册可能会发生变化,特别是在一个学期的休息期间。6 个月后的学生名单可能与现在的学生名单只有 70% 的重合。真的,你应该等到最后的实际时刻。

But what constitutes a worthy “Day X”? It might be a test. But if it’s your test, you may not have been listening. Your test may just be arbitrarily punishing some kids for forgetting a little sooner than others. However, if it’s an external test, with high stakes for you and your students, then it could be a worthy Day X indeed. For me, Day X is the day of the big state test — the one used to compare students to students, teachers to teachers, and schools to schools.

但是,什么才是值得的 "第X天"?它可能是一个测试。但如果是你的考试,你可能没有听进去。你的测试可能只是武断地惩罚一些孩子,因为他们比其他人忘得早一点。然而,如果这是一个外部测试,对你和你的学生都有很高的风险,那么它确实可能是一个值得一试的第X天。对我来说,第X天是大型州级考试的日子——用来比较学生与学生、教师与教师、学校与学校的考试。

When your students do well on an external test, though, please keep a healthy perspective. A high test score doesn’t mean they can do the hard things now and forever. It means they were able to earn a high test score on Day X. They will forget almost all of it afterwards. But you will have given them their best chance to signal to others that they can learn hard things, and that you can teach them hard things, and that your school has teachers who can teach hard things.

不过,当你的学生在外部测试中表现出色时,请保持一个健康的视角。一个高的考试分数并不意味着他们现在和将来都能做那些难事。这意味着他们能够在第X天获得一个高的测试分数,之后他们几乎会忘记所有的事情。但是,你将给他们最好的机会,向别人表明他们可以学习困难的事情,你可以教他们困难的事情,你的学校有可以教困难事情的老师。

Day X doesn’t have to be a test. If you’re optimizing for brain change that persists after they forget all of your content, Day X could be an immersive event. Maybe your Spanish class is going to Madrid. You know they will have a deeper experience if you can bring their vocabulary to a peak of richness and automaticity on the eve of departure. Yes, they’ll still forget almost all the words later. But they might retain a glimpse of how the world looked when seen through another language.

第X天不一定是一个测试。如果你在优化大脑的变化,在他们忘记你所有的内容后仍然存在,第X天可以是一个沉浸式的活动。也许你的西班牙语课要去马德里。你知道,如果你能在出发前夕将他们的词汇量提高到丰富性和自动性的顶峰,他们会有更深刻的体验。是的,他们以后还是会忘记几乎所有的单词。但他们可能会保留一丝通过另一种语言看世界时的样子。

Maybe your event is smaller. A virtual trip. An in-class conversation day where we pretend we’re at the beach (“¡En la Playa!”). Maybe their long-term takeaway will be an appreciation for how different languages use different grammars, which is not something most people even consider until they’ve studied a second language. Get their mental gears turning hard enough, and they might even see grammar as an arbitrary construct with tunable parameters and tradeoffs that influence what can be communicated easily. Maybe they’ll independently rediscover the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. But they’re not going to remember how to say ‘sand’. Nope. ‘Shark’, maybe (¡Tiburón!). But you can’t predict this, and it’s probably not worth the effort to try.

也许你的活动比较小。一次虚拟旅行。一个课内对话日,我们假装自己在海滩上("En la Playa!")。也许他们的长期收获将是对不同语言如何使用不同语法的欣赏,这是大多数人在学习第二语言之前都不会考虑的事情。让他们的心理齿轮转动得足够厉害,他们甚至可能把语法看作是一种任意的结构,具有可调整的参数和权衡,影响到可以轻松交流的内容。也许他们会独立地重新发现萨皮尔-霍夫假设。但他们不会记得如何说 "沙子"。不,"鲨鱼",也许("Tiburón!")。但你无法预测这一点,而且可能也不值得努力去尝试。

But maybe you’re not teaching a foreign language. No matter your subject, Day X could be any conceptually demanding lesson or unit that is difficult to even talk about without fluency in a given set of terms. These aren’t very common in 10th Grade English, though they come up more often in my Creative Writing class. In these cases, however, the dependent terms are conceptually rich enough that they don’t lend themselves very well to cards, and I find it’s better to just quickly re-teach them in front of the lessons that use them. “Remember how we said...”

但也许你不是在教外语。无论你的科目是什么,第X天可能是任何概念上要求很高的课程或单元,如果不流利地掌握一套术语,甚至很难讨论。这种情况在 10 年级英语课上并不常见,不过在我的创意写作课上更经常出现。然而,在这些情况下,从属术语在概念上足够丰富,以至于它们不能很好地用于卡片,我发现最好是在使用它们的课程前快速重新教授它们。"记得我们是怎么说的吗......"

How I currently use classroom SRS

我目前如何使用课堂 SRS

As you may have guessed, I’ve radically scaled back my usage of classroom SRS since those first three years. In fact, for the last four years, I’ve only used it during a two-to-three month span leading up to the state test. And for the last two of those years, I’ve only used it for word fragments. I’m very unlikely to abandon its use for word fragments, though, because the most important thing I teach my students by using SRS is the existence of SRS. Word fragments are my favorite way to demonstrate how efficient study time can be. I add no more than about ten cards per week, which means that most days’ study takes less than two minutes. (This is good, because my own enthusiasm now begins to flag by the two minute mark.) I give very short quizzes on the fragments so they can do well on them and see how a little study can have a big payoff. (Remember that most of my students don’t ever study on their own.)

你可能已经猜到了,从头三年开始,我已经从根本上减少了对课堂 SRS 的使用。事实上,在过去的四年里,我只在州考试前的两到三个月内使用过它。而在这些年中的最后两年,我只将它用于单词片段。不过,我不太可能放弃对单词片段的使用,因为我通过使用 SRS 教给学生的最重要的东西是 SRS 的存在。词汇片段是我最喜欢的展示学习时间效率的方式。我每周增加的卡片不超过 10 张,这意味着大多数天的学习时间不到两分钟。(这很好,因为我自己的热情现在到两分钟的时候就开始下降了)。我对片段进行了非常简短的测验,这样他们就能在这些片段上做得很好,并看到小小的学习可以有很大的回报。(请记住,我的大多数学生都没有自己学习过。)

I’m still using Anki, with different profiles for each class. I run the review in a call-and-response style, where I show and say the card, and they know to simply shout out the answer. On a good day, it becomes a kind of chant. The number, speed, accuracy, and confidence of the responding voices tells me which button to press, and there’s usually a bellwether student I can listen for as I make my decision. Because I’m striving for very high automaticity, I almost always press either 2 (the shortest affirmative next-study delay) or 1 (the negative start-it-from-scratch button).

我仍然在使用 Anki,每个班都有不同的配置文件。我以呼唤和回应的方式进行复习,我出示并说出卡片,他们知道要简单地喊出答案。在一个好的日子里,这成了一种颂歌。响应的声音的数量、速度、准确性和信心告诉我应该按哪个按钮,而且通常有一个风向标学生,我可以在做决定时倾听。因为我正在努力争取非常高的自动性,所以我几乎总是按 2(最短且积极的下一次学习间隔)或 1(消极的从头开始按钮)。

My students mostly like the call-and-response flow, as archaic as it sounds, and I will refer you to an older footnote about that time I observed a traditional one-room Mennonite schoolhouse:

I once had the privilege of observing part of a lesson in a traditional Mennonite one-room schoolhouse. I don't speak a word of Low German, but it was clear the kids knew whatever it was they were drilling as they stood up and recited together. Most striking was the fact that they were all on the same page. There were no stragglers spacing out, slumped over, dozing off. The teacher could confidently build up to whatever came next without fear of leaving anyone behind.

我的学生大多喜欢呼唤和回应的流程,虽然听起来很陈旧,我将向你介绍一个较早的脚注关于那次我观察一个传统的单间门诺教派的校舍:

我曾经有幸在一个传统的门诺派单间校舍里观察了部分课程。我不会说一句低级德语,但很明显,孩子们知道他们在钻研什么,因为他们站起来一起背诵。最引人注目的是,他们都在同一页上。没有落单的人,也没有耷拉着脑袋打瞌睡的人。老师可以自信地进行下一步的训练,而不用担心会有任何人掉队。

For at least a minute or two every day, even worldly American kids can enjoy the routine. As I put it elsewhere in that Second Year report, “They enjoy the validation they get with each chance to confirm that they remember something. They enjoy going with the flow of a whole class doing the same thing. They enjoy the respite of learning on rails for a change, without any expectation that they take initiative or parse instructions.”

每天至少有一两分钟,即使是世俗的美国孩子也能享受这种常规。正如我在第二年的报告中所说的那样,"他们喜欢每次有机会确认他们记住了什么,就会得到验证。他们喜欢随波逐流,整个班级都在做同样的事情。他们享受在轨道上学习的喘息之机,而不期望自己主动或解析指令。"

It probably goes without saying, but this call-and-response format only works well with cards with a very short answer that can be recalled very quickly. This is why I now only use SRS for word fragments. If I taught a foreign language, or even a lower-grade reading class with more basic vocab words, I would be using it more. My wife taught high school Spanish for a number of years, experimented with SRS, and is on the record as saying Duolingo deserves to eat the world. Anyone she could get to use it independently didn’t really need her class to do well on the final assessments.

这可能不用说,但这种呼唤和回应的形式只适用于答案非常简短、可以很快回忆起来的卡片。这就是为什么我现在只把 SRS 用于单词片段。如果我教的是外语,或者甚至是有更多基本词汇的低年级阅读课,我就会更多地使用它。我的妻子在高中教过几年西班牙语,尝试过 SRS,并公开表示 Duolingo 应该占领全世界。她能让任何一个人独立使用它的人都不太需要她的课,而在期末考试中取得好成绩。

After the state test, my students will forget almost all of their word fragments. That is the way of things. Ashes to ashes, circle of life, or, to get back to my controlling analogy, “All drains lead to the ocean, kid.” What I’m hoping will remain is an updated appreciation for what a little regular study can do, and a vague recollection that there are these apps out there that are, you know, like smart flash cards, that make it fast to memorize stuff.

在州考之后,我的学生几乎会忘记所有的单词片段。这就是事物的发展规律。尘归尘,土归土,生命的轮回,或者,回到我的控制比喻,"所有的排水管道都通向大海,孩子。" 我希望留下的是对一点常规学习所能起到的作用的最新赞赏,以及模糊地记得有这些应用程序,你知道,就像智能抽认卡一样,使记忆东西变得迅速。

Against apathy, toward apprenticeship

反对默认,走向学徒制

I’m nearing the end of Part 1, which means I’m nearing the end of my labors on this post, since Part 2 was mostly written five years ago. As writing projects go, I have found this one extraordinarily difficult. Over the course of its creation, I have pooped five times. It wants to be a book (or at least a blog), as everything I say tries to come out as a chapter of explanation having little to do with SRS.

我已经接近第一部分的结尾,这意味着我在这篇文章上的工作已经接近尾声,因为第二部分大部分是五年前写的。作为写作项目,我发现这个项目特别困难。在创作过程中,我已经大便了 5 次。它想成为一本书(或至少是一个博客),因为我说的每一句话都想作为与 SRS 没有什么关系的解释章节来发表。

Well, I’m now going to indulge in several paragraphs where I don’t tie it back to SRS, so I can tell you the story of how I reinvented myself after my third year of spaced repetition software in the classroom. This included moving to a new school where I would have greater freedom to pursue my evolving views about learning. For what it’s worth, this story at least starts with SRS.

好吧,我现在要沉浸在几个段落中,不把它与 SRS 联系起来,所以我可以告诉你我是如何在课堂上使用间隔重复软件的第三年后重新塑造自己的故事。这包括搬到一所新的学校,在那里我将有更大的自由来追求我对学习不断变化的看法。就其价值而言,这个故事至少开始于 SRS。

You see, it was during those dangerously long classroom Anki sessions six and seven years ago that I honed my sensitivity to students’ moods, to my own mood, and to how these feed off of each other. Sustaining a session without losing the room was like magnetically confining hot deuterium plasma — dicey, volatile, but occasionally, mysteriously, over unity. I came to view anti-apathetic moods as a kind of energy that can be harnessed to do work and to create new energy.

你看,正是在六七年前那些危险的漫长的 Anki 课堂上,我磨练出了对学生情绪和我自己情绪的敏感度,以及这些情绪是如何相互影响的。在不失去教室的情况下维持一节课,就像用磁力限制热氘等离子体一样——危险、不稳定,但偶尔也会神秘地超过统一性。

Apathy, you may recall, is the true enemy. I’ve always known that. I called her out five years ago, but soon came to realize I had been fighting her on the wrong front.

你可能记得,漠然是真正的敌人。我一直都知道这一点。五年前我叫她出来,但很快就意识到我一直在错误的战线上与她作战。

I had been preoccupied by the fact that students who don’t care won't activate enough of their brain to get any benefits from our daily review. To be fair, that is a problem, if I’m trying to prime them for success at a Day X event. But the more insidious issue is that a student in the thrall of Apathy won’t be churning their mental gears on any of the content I may have tricked them into learning, which means they’ll just forget it all without having made any lasting changes to their models. That’s not just an Anki-time problem. That’s an all-the-time problem. If they don’t engage with anything, they don’t keep anything.

我一直在想,那些不关心的学生不会激活他们的大脑,无法从我们的日常复习中获得任何好处。公平地说,这是一个问题,如果我试图让他们在第X天的活动中取得成功。但更隐蔽的问题是,处于漠然状态的学生不会对我可能诱导他们学习的任何内容进行头脑风暴,这意味着他们只会忘记这些内容,而不会对他们的模型做出任何持久的改变。这不仅仅是一个 Anki 时间的问题。这也是所有时间的问题。如果他们不参与任何事情,他们就不会保留任何东西。

I set off on a holy quest for anti-apathetic energy.

我开始了对反漠然能量的神圣追求。

My errantry led me, for a time, to study stand-up comedy, not just because humor creates energy, but because a big part of that craft is an acting trick where you deliver incredibly polished lines in a way that sounds like you’re coming up with them right there in that moment. Perceived spontaneity is a powerful source of energy even more versatile than humor.

我的误入歧途使我一度学习单口相声,不仅是因为幽默能创造能量,而且因为这种技艺的很大一部分是一种表演技巧,你以一种听起来就像你在那一刻想出来的方式,说出令人难以置信的精炼台词。

I don’t know if I learned much about scripted spontaneity that I could articulate, but I felt like some of it rubbed off on me just by watching the experts closely over extended periods. And you know what? A lecture isn’t so different from a bit. A lesson isn’t so different from a set. A single changed word, a half-second delay, a subtle shift in facial expression can completely change the way the moment feels to the audience class. And like a comedian workshopping new material on the road, I could use the fact that I might teach the same lesson five times in one day to test variations, trying to provoke more engagement, better questions, bigger laughs.

我不知道我是否学到了很多我可以表达的关于剧本的自发性的东西,但我觉得仅仅是通过长时间密切观察专家,我就感受到了其中的一些东西。而且你知道吗?讲座和位子并没有什么不同。一堂课和一套节目并没有什么不同。一个改变了的词,一个半秒的延迟,一个面部表情的微妙变化,都可以完全改变观众的感受。就像喜剧演员在路上研讨新材料一样,我可以利用我可能在一天内讲五次同样的课的事实来测试变化,试图激起更多的参与,更好的问题,更大的笑声。

Equally important: I recognized that the process of refining the performance art was fun for me, and that my own engagement was the most powerful source of classroom energy. I could transmit it to my students, and maybe even get some energy back from them while I directed some of it into activity that would get their mental gears turning. Instead of burning out, I could burn brighter, and longer. On a good day, it became self-sustaining. On a great day, it could go supercritical, sending me home after my last class with my head spinning in a buzz of positive vibes and deep thoughts.

同样重要的是:我认识到改进表演艺术的过程对我来说很有趣,而且我自己的参与是课堂能量的最有力来源。我可以把它传递给我的学生,甚至可以从他们那里得到一些能量,同时我把一些能量引导到可以让他们的精神齿轮转动的活动中。我可以烧得更亮、更久,而不是烧得精疲力尽。在一个好的日子里,它可以自我维持。在一个伟大的日子里,它可以变成超临界状态,让我在最后一堂课后带着我的头脑在积极的氛围和深刻的思想中旋转着回家。

During this same era, as part of my ongoing study of creative writing, I was binge-listening to interviews with television writers. One pattern that struck me was that it wasn’t too uncommon for someone to just kind of find themselves working in that highly rarefied field simply because they had spent a lot of time around others who were already doing it. Without any organized instruction, they picked up on how it worked.

在同一时期,作为我正在进行的创意写作研究的一部分,我正在狂听电视作家的采访。让我印象深刻的一个模式是,一个人发现自己在这个高度稀缺的领域工作并不罕见,只是因为他们花了很多时间在那些已经在做的人身边。没有任何有组织的指导,他们就学会了如何工作。

Did you catch it? That was twice that I had noticed how arcane expertise can rub off on people through prolonged proximity. That got me thinking about the German Apprenticeship Model, and its medieval — nay, prehistoric — roots. It’s how we used to learn everything, right? We followed mama out to the berry bushes, and papa out to the hunting grounds. The fact that it seemed to work for television writers told me that apprenticeship wasn’t just for blue collar skills.

你明白了吗?那是我两次注意到神秘的专业知识是如何通过长期的接近而蹭到人们身上的。这让我想到了德国学徒模式,以及它的中世纪——不,是史前——的根源。我们过去就是这样学习一切的,对吗?我们跟着妈妈到浆果丛中去,跟着爸爸到狩猎场去。这对电视编剧来说似乎很有效,这一事实告诉我,学徒制并不只是针对蓝领技能。

So, with the longer leash I enjoyed under my new bosses, I decided to move my instructional style closer to something resembling an apprenticeship where I mentored groups of 20-30 padawans in my arcane expertise.

因此,由于我在新老板手下享有较长的自由,我决定将我的教学风格向类似于学徒制的方向发展,在那里我指导 20-30 名学徒学习我的神秘专业知识。

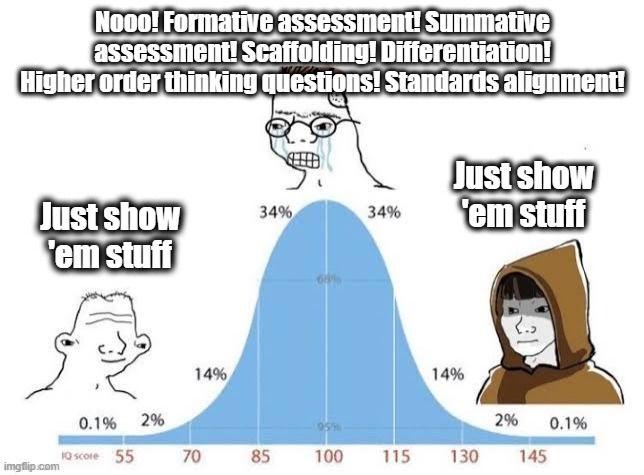

Yeah, I jumped on a trendy meme. Note my careful word choice: ‘show’, not ‘tell’. This, to me, is the defining action in mentor-apprentice relationships.

是的,我喜欢流行的模因。请注意,我谨慎地选择了“show”,而不是“tell”。对我来说,这是师徒关系中的决定性行动。

By switching schools, I lost my interactive whiteboard. So I replaced it with something even better: an extra computer on a make-shift stand-up desk (a narrow kitchen prep cart with fold-out boards.). A cheap second-hand monitor could face me while I mirrored that screen to the projector. Now I could do what I had seen coders do at instructional meet-ups: face the class while typing.

由于换了学校,我失去了我的互动白板。所以我用更好的东西代替了它:一台额外的电脑放在一个临时的站立式办公桌上(一个狭窄的厨房准备车,上面有折叠板)。一台便宜的二手显示器可以面对我,而我把屏幕镜像到投影仪上。现在我可以做我在教学会议上看到的编码员所做的事了:在打字的时候面对全班同学。

This meant I could show students what I do as a writer in real time, thinking out loud and watching their reactions as I typed. This could easily bore them, of course, but with strong energy-fu, old-school touch typing speed, and face-to-face interaction, I can pull it off more often than you might expect. On a good day, they find it fascinating. On one very special occasion each year, I do it for the full period, writing a 400+ word essay from scratch in 40 minutes with no prior knowledge of the prompt. Students have to hold their questions that day, and instead take observation notes, which become fodder for an extended debriefing discussion the next day.

这意味着我可以实时向学生展示我作为一个作家的工作,在我打字的时候大声思考并观察他们的反应。当然,这很容易让他们感到厌烦,但凭借强大的精力、老式的触摸打字速度和面对面的互动,我可以比你想象的更经常地完成这个任务。在一个好的日子里,他们觉得这很吸引人。在每年的一个非常特殊的场合,我整个时期都在做这件事,在 40 分钟内从头开始写一篇 400 多字的文章,事先对提示一无所知。学生们必须在当天保留他们的问题,而是做观察笔记,这成为第二天扩展汇报讨论的素材。

The most important thing I’ve learned from those debriefings is that everyone can pick up something from a holistic demonstration like that, regardless of their skill level. An advanced student might ask about my bracket substitution of a pronoun in a quote. An average student might say, “You used a lot of small and medium-sized body paragraphs instead of three big ones.” A sub-level student might say, “You didn’t like it if you used the same word too soon after you used it before.” And I always seem to get at least one surprising question about something I never would have thought to teach them, like, “How did you suck words into your cursor?” Then I’m like, “Oh, let me show you the difference between the Backspace and Delete keys…”

我从这些汇报中学到的最重要的东西是,每个人都能从这样的整体示范中获得一些东西,不管他们的技能水平如何。一个高水平的学生可能会问为什么我在引文中用括号替换了一个代词。一个普通的学生可能会说,"你用了很多中小型的正文段落,而不是三个大段落"。一个次等水平的学生可能会说,"你不喜欢在之前使用同一个词后过早地使用它"。而且我似乎总能得到至少一个令人惊讶的问题,关于一些我从未想过要教他们的东西,比如,"你是如何将单词吸进光标的?" 然后我就会说:"哦,让我告诉你退格键和删除键的区别......"

Did I make them memorize anything with that “lesson”? Nah. Did they make lasting updates to their mental models? Probably! Are you thinking of asking me, “But how do you test them on it?” Because if you are, then you really haven’t been paying attention!

我用那堂 "课" 让他们记住了什么吗?没有。他们对自己的心理模型进行了持久的更新吗?可能是吧!你是不是想问我,"但你是如何测试他们的?" 因为如果你是的话,那你就真的没有注意了!"。

There’s plenty more to be said about apprenticeship, but I think you get the idea, and this is still nominally an essay about classroom SRS.

关于学徒制还有很多可说的,但我想你会明白的,而且这在名义上还是一篇关于课堂 SRS 的文章。

If I had to summarize my self-reinvention in too many words, I would say that I’m now optimizing for “good days” at the high-energy intersection of “engaging for me”, “engaging for them”, and “conducive to lasting and worthwhile updates to their mental models”, with less regard for curricular scope and sequence.

如果我必须用太多的话来总结我的自我革新,我会说我现在正在优化 "好日子",在 "吸引我"、"吸引他们 "和 "有利于持久和有价值地更新他们的心理模型 "的高能量交叉点,而不太考虑课程范围和顺序。

In practice, this means… well, a lot of things. But it’s time I pinch off Part 1. That, “or get off the pot,” as they say.

在实践中,这意味着......嗯,很多事情。但现在是我结束第一部分的时候了。他们说,“或者滚开。”。

Part 2: A Third Year of Spaced Repetition Software in the Classroom (2017)

第二部分:在课堂上使用间隔重复软件的第三年(2017)

[In this excavated report, text in brackets in commentary I’m adding in 2021. Anything out of the brackets is direct from my 2017 draft, or constructed from my notes to fit the perspective I had at the time.]

[在这份发掘的报告中,括号内的文字是我在 2021 年添加的评论。括号外的内容是直接来自我的 2017 年草案,或根据我的笔记构建的,以符合我当时的观点。]

Synopsis and disclosure

概要和披露

I tried the obvious thing this year. Instead of game show-style whole-class front-of-the-room Anki, I arranged for every student to be able to independently study material I created in Cerego, both in and out of class.

今年我尝试了显而易见的事情。而不是游戏表演式的教室前面的全班同学Anki,我安排每个学生都能独立学习我在[Cerego]中创作的材料(https://www.cerego.com/),课内外。

今年,我尝试了一个显而易见的做法。我安排每个学生在课上和课下都能独立学习我在 Cerego 中创建的材料,而不是游戏表演式的全班 Anki。

Disclosure: Cerego provided me a free license for the year in exchange for some detailed feedback, which I gave them. This feedback was mostly about user interface issues and reports, the latter of which required some ugly scripting on my end to get numbers I found useful. As the Cerego team seemed to be rapidly iterating, I imagine they have made many changes and improvements to their app since 2017, though I have not used it since. Please keep this in mind as you read these years-old notes.]

披露:Cerego 为我提供了一年的免费许可,以换取我给他们的一些详细反馈。这些反馈主要是关于用户界面问题和报告,后者需要我编写一些丑陋的脚本来获得我认为有用的数字。由于Cerego 团队似乎在快速迭代,我想象他们自 2017 年以来对其应用程序进行了许多修改和改进,尽管我后来没有使用它。当你阅读这些多年前的笔记时,请牢记这一点]。

Despite many small hang-ups, I was pleased with the Cerego’s features and reliability. In exchange for a great deal of up-front effort, it gave me a unique window into student engagement and progress. Consequently, it proved to be an overwhelmingly potent tool for winning “the blame game”, although I eventually came to feel uneasy about using this power.

尽管有许多小问题,我对 Cerego 的功能和可靠性感到满意。作为对大量前期工作的回报,它为我提供了一个了解学生参与和进步的独特窗口。因此,它被证明是赢得 "指责游戏" 的一个非常有力的工具,尽管我最终对使用这种力量感到不安。

Longer-term learning outcomes seemed, on average, to be slightly worse than with the whole-class Anki method. While highly motivated students benefited from being able to study more aggressively and efficiently than before -- and their objective scores were higher than ever -- their learning seemed less transferable to more authentic contexts. Students of lower motivation, while seeming to get little from either approach, got even less from this digital 1:1 method, and their slump accounts for the overall decline.

平均而言,长期的学习成果似乎比全班同学使用 Anki 的方法略差。虽然积极性高的学生因能够比以前更积极、更有效地学习而受益——他们的目标分数也比以前高——但他们的学习似乎不太能够转移到更真实的环境中。积极性差的学生,虽然从任何一种方法中似乎都没有得到什么,但从这种数字化一对一的方法中得到的就更少了,他们的低迷导致了整体的下降。

Setup

设置

I taught a mix of regular (not honors) 9th and 10th English classes again, but over the summer of 2016 I was invited to move my classroom into an unusually-spacious converted computer lab in which 16 older desktop PCs were kindly left at my request. I had these arranged facing the sides of the room so I could see all screens easily. I allocated those PC seats on a semi-permanent basis as needed and requested. The balance of students sat at normal desks and used their phones for study.

我再次教授普通(不是优等生)9 年级和 10 年级的英语课,但在 2016 年夏天,我被邀请将我的教室搬到一个异常宽敞的改装计算机实验室,在我的要求下,16 台老式台式电脑被好心地留在那里。我把这些电脑安排在房间的两侧,这样我可以很容易地看到所有的屏幕。我根据需要和要求半永久性地分配这些电脑座位。其余的学生则坐在普通的桌子上,用他们的手机学习。

This came with challenges. School WiFi was officially off-limits to students (though many always had the password anyway), and many students said they were at the whim of data caps they regularly pushed up against. Their phones, in most cases, were a generation or three behind state-of-the-art, with degraded batteries and exhausted storage capacity. A few students had difficulty even making room for the Cerego app that first week.

这带来了挑战。学校的 WiFi 对学生来说是正式的禁区(尽管许多人总是有密码),许多学生说,他们经常受到数据上限的影响。在大多数情况下,他们的手机已经落后于最先进的一代或三代,电池已经退化,存储容量已经耗尽。有几个学生在第一周甚至难以为 Cerego 应用程序腾出空间。

While our setup was marginal, between the PCs and phones, we only rarely ran into a situation where not everyone could be studying at the same time.

虽然我们的设备在边缘,在个人电脑和手机之间,我们只是很少遇到不是每个人都能在同一时间学习的情况。

On the software side, it must be said that, for all its features, Cerego wasn’t designed for my specific use case. The company’s featured customers are business and colleges, who use the product as part of packaged training programs and distance learning courses. Importantly, the app favors adding content into the learner’s study rotation in blocks, on the learner’s own schedule, rather than making it on the fly and trickling it immediately. It was also not designed to give a teacher “panopticon”-style real-time monitoring, nor to thwart adversarial users who want to look studious without studying.

在软件方面,必须指出的是,尽管 Cerego 具有各种功能,但它并不是为我的特定使用情况而设计的。该公司的主要客户是企业和学院,他们将该产品作为成套培训计划和远程学习课程的一部分。重要的是,这款应用更倾向于按照学习者自己的时间表,以块为单位将内容添加到学习者的学习循环中,而不是匆忙地制作内容并添加到学习循环中。它的设计也不是为了给教师提供 "全景图" 式的实时监控,也不是为了挫败那些想在不学习的情况下看起来很好学的敌对用户。

Procedure

程序

Before the start of each school day, I would consider the previous day’s lesson content and add to the relevant Cerego study sets as appropriate. This process could be lumpy and not necessarily daily; some lessons invited a great deal of suitable content, and others none at all. Content additions were also far more common first semester than second semester, as I intentionally front-loaded material to maximize the time we would have to reinforce and apply it. During an average week where I added cards, we probably averaged about 50 additions. [ ! ]

在每个工作日开始之前,我会考虑前一天的课程内容,并酌情添加到相关的 Cerego 学习集中。这个过程可能是不稳定的,也不一定是每天的;有些课程会引入大量合适的内容,而有些则完全没有。第一学期的内容增加也比第二学期的多,因为我故意把材料放在前面,以最大限度地增加我们巩固和应用材料的时间。在我添加卡片的平均一周内,我们大概平均添加了50张卡片。[ ! ]

With a prominent timer at the front of the room, I allocated 10-12 minutes at the start of every 57 min class period as specially designated “Cerego Time”. During Cerego Time, I would periodically patrol the room to ensure students were on task and to provide support.

我在教室前面放了一个醒目的计时器,在每节 57 分钟的课开始时分配 10-12 分钟作为特别指定的 "Cerego 时间"。在 Cerego 时间里,我会定期在教室里巡逻,以确保学生完成任务并提供支持。

Students were allowed to read a pleasure-reading book during this time instead, if they chose. This allowance was most obviously meant for anyone with extra time after catching up with their study, but I wasn’t about to interfere with any teenager reading a book on their own volition. Not all regular readers (2-5 per class) were conscientious Cerego-ers.

如果学生选择的话,他们可以在这段时间内阅读一本有趣的书。这一允许显然是为任何在赶上学习后有额外时间的人准备的,但我并不打算干涉任何青少年按自己的意愿阅读一本书。并非所有的普通读者(每班 2-5 人)都是自觉的 Cerego-ers。

Students were strongly encouraged to also use Cerego outside of class whenever the app recommended, if they wanted maximal retention for minimal time spent.

强烈鼓励学生在课外使用 Cerego 应用程序,如果他们希望用最少的时间保持最大的保留率。

About once a week, usually without warning, I would give a ten question multiple choice quiz that could include questions directly taken from any content that had been in Cerego for at least a week, no matter how old. This was a multiple choice quiz done digitally in Canvas. Before I put the grade into my book, I would add a 10% adjustment (not to exceed 100%), respecting the wisdom that aggressive study sees diminishing returns as one approaches a goal of 100% retention on large bodies of knowledge. My students were aware of this free 10% and my reasoning behind it.

大约每周一次,通常是在没有警告的情况下,我会做一个有 10 个问题的选择题测验,其中包括直接从 Cerego 中至少有一周的内容中抽取的问题,不管是多老的问题。这是一个在 Canvas 中以数字方式进行的选择题测验。在我把成绩记在本子上之前,我会加上 10% 的调整(不超过100%),这是对积极学习的智慧的尊重,因为当一个人接近 100% 保留大型知识体系的目标时,他的回报会越来越少。我的学生们都知道这个免费的10%和我背后的理由。

To account for students just joining my class at the start of second semester, and for those who inevitably studied nothing for the seventeen calendar days between semesters — and even for those simply desperate for a fresh start — I had a lengthy grace period of sorts in January and February. Older stuff was temporarily not included in the “quizzable” question pool. I posted dates for when I would consider each old set fair game again; every week or two, a set would find itself back in the pool according to this schedule, and stay there for the rest of the year.

为了照顾那些在第二学期开始时刚加入我的班级的学生,以及那些在两学期之间的 17 天里不可避免地没有学习的学生——甚至那些仅仅是急于重新开始的学生——我在 1 月和 2 月有一个很长的宽限期。旧的东西暂时不包括在 "可测验" 的题库中。我公布了我认为每套旧题的公平竞争日期;每隔一两个星期,就会有一套题按照这个时间表回到题库中,并在今年余下的时间里保持在那里。

I did not use Cerego stats directly for any kind of grade, instead using my Canvas quizzes for this. My reasons:

我没有直接用 Cerego 的数据来评分,而是用我的 Canvas 测验来评分。我的理由:

I wasn’t sure every student would consistently be able to use the app, and didn’t want to deal with the push-back from students and parents claiming (honestly or otherwise) insurmountable tech obstacles to using Cerego outside of class.

我不确定每个学生都能一直使用这个应用程序,也不想面对学生和家长的强烈反对,他们声称(诚实地或以其他方式)在课外使用 Cerego 存在无法克服的技术障碍。

Due to limitations in Cerego’s reporting, I wasn’t sure how to regularly compute a fair grade based on Cerego stats.

由于 Cerego 报告的局限性,我不确定如何根据 Cerego 的统计数据定期计算公平分数。

I wasn’t sure how far I would be able to trust that a student’s stats weren’t being run up by a smarter friend using the app on their behalf.

我不确定我能够在多大程度上相信学生的统计资料没有被一个更聪明的朋友以他们的名义使用该应用程序而提高。

I didn’t want to discourage students from using Cerego Time to instead read their pleasure books (a habit of immense, scientifically-backed value that I do everything I can to promote).

我不想阻止学生利用 Cerego 时间来阅读他们的快乐书籍(这种习惯具有巨大的、有科学依据的价值,我尽我所能来推广)。

I didn’t want to give the impression that Cerego is necessarily the best or only way to study, but instead to make it clear that knowing the content was their responsibility, however they chose to do it; my providing them with Cerego cards and time to study them was simply a function of my being a Really Nice Guy.

我不想给人这样一种印象,认为Cerego一定是最好的或唯一的学习方法,而是想明确地表明,了解内容是他们的责任,不管他们选择做什么;我给他们提供了 Cerego 卡片和时间来学习它们,这仅仅是因为我是一个非常好的人。

Points of friction

摩擦点

This section is not a critique of Cerego specifically, but rather a reminder that classroom technology is not inherently good. The mythical 1:1 student tech ratio doesn’t suddenly make impossible dreams reality, and in fact comes with ongoing costs that must be weighed against the benefits. Here were some points of friction I encountered:

本节不是对 Cerego 的具体批评,而是提醒大家,课堂技术并非天生就是好事。神话般的一对一学生技术比例并不会突然让不可能的梦想成为现实,事实上,它还伴随着持续的成本,必须与收益相权衡。以下是我遇到的一些摩擦点:

Forgotten login information for the school PCs or Cerego.

忘记了学校 PC 或 Cerego 的登录信息。

Slow startup, login, and load times on outdated equipment. [Fun fact: I’ve found that as my current school cuts down on the need for different logins through Clever, they create a separate problem of longer and more fragile authentication chains — handshaking from one site to another — that can fail on slow machines or under spotty WiFi.]

在过时的设备上,启动、登录和加载时间缓慢。[有趣的事实:我发现我现在的学校通过 Clever 减少了不同的登录需求,他们创造了一个单独的问题,即更长、更脆弱的认证链——从一个网站到另一个网站的握手——在缓慢的机器上或在斑驳的WiFi下可能失败。]

Old or abused keyboards and mice that intermittently fail.

旧的或被滥用的键盘和鼠标间歇性地失灵。

The occasional bigger problem, like a blown power supply.

偶尔会出现更大的问题,比如停电。

For phone users: discharged, confiscated, lost, or broken devices.

适用于手机用户:没电、没收、丢失或损坏设备。

Distractions and inappropriate behaviors that wouldn’t be possible if students didn’t have their own screen to command.

分散注意力和不当行为,如果学生没有自己的屏幕来操控,就不可能出现这种情况。

All of the above adds up to a kind of tax on your time and energy, even when you have enough respect from your students to minimize deliberate abuse. (I had maybe 2-3 bad eggs during the year committing occasional acts of minor sabotage.) Moreover, every possible point of friction becomes amplified by a student who doesn’t feel getting to the objective, like a child who finds an hour’s worth of yak shaving to do whenever bedtime rolls around.

所有上述情况加起来就是对你的时间和精力的一种征税,即使你得到了学生足够的尊重,以减少故意的滥用。(在这一年里,我可能有 2-3 个坏蛋偶尔会进行一些小的破坏活动)。此外,每一个可能的摩擦点都会被一个觉得达不到目标的学生放大,就像一个孩子,每当睡觉时间一到,就会发现有一个小时的牦牛剃毛要做。

Problems with multiple-choice study cards

多项选择学习卡片的问题

Unlike Anki and other personal-use SRS, where the user self-assesses performance and collaborates with the app to schedule the next review, apps like Cerego are built to measure retention objectively. This changes how study cards have to be constructed. Although options [even in 2017] are varied, the most practical and straightforward method is usually a “front” side card with a question or term and a “back” side of multiple-choice responses.

与 Anki 和其他个人使用的 SRS(用户自我评估成绩并与应用合作安排下一次复习)不同,像 Cerego 这样的应用程序是为了客观地测量保留率。这改变了学习卡片的构建方式。虽然[即使在 2017年]选项也是多种多样的,但最实用和最直接的方法通常是 "正面 "卡片上有一个问题或术语,"背面 "则是选项。

Some problems with multiple-choice format:

多项选择格式的一些问题:

Responding to a multiple-choice question (or any kind of question) takes more time than pressing a self-assessment button.

回答多项选择题(或任何类型的问题)比按下一个自我评估按钮需要更多时间。

In general, it’s more work to create study cards that can be assessed by the app. This is true even in the ideal case, which for Cerego is when you can assign a set of cards where the correct answer in one card can automatically become a multiple-choice distractor (wrong answer) for other cards in the set. But many cases are not ideal, and the only plausible distractors will be ones you add manually.

一般来说,创建可由应用程序评估的学习卡片是比较费事的。即使在理想的情况下也是如此,对于 Cerego 来说,当你可以分配一组卡片,其中一张卡片的正确答案可以自动成为这组卡片中其他卡片的多选干扰项(错误答案)。但是很多情况并不理想,唯一合理的干扰因素应该是你手动添加的。

Students can get confused when distractors contaminate tenuous mental associations. This is a well-studied effect with testing in general, and I had one student (motivated, but lower IQ) who I feel was positively ruined by it this year.

当分散注意力的因素污染了脆弱的心理联想时,学生会感到困惑。这是对一般测试的一个很好的研究结果,我有一个学生(有上进心,但智商较低),我觉得他今年被这个问题毁了。

Students mostly don’t try to recall the answer before looking at multiple-choice options, instead defaulting to the following heuristic: “Look for an answer that feels right -- if none do, press ‘None of the above’”. This is a problem, because the act of trying to recall the specific thing is known to be the critical step that reinforces the memory; in contrast, merely recognizing familiar facts (as when “going over notes”) is known to give students false confidence.

学生们在看多选题之前大多不会尝试回忆答案,而是默认以下启发式方法:"寻找一个感觉正确的答案--如果没有,就按'以上没有正确答案'"。这是一个问题,因为尝试回忆具体事物的行为被认为是强化记忆的关键步骤;相反,仅仅认识熟悉的事实(如 "翻阅笔记 "时)被认为会给学生带来错误的信心。

I gave my Cerego contacts some ideas I had for minimizing some of the downsides of multiple-choice. Because my students were largely deaf to my pleading that the “front” card screen — the one containing only the question — is where the learning actually happens, there could be a mandatory (or at least default, opt-out) short delay on that screen, especially when the app detects inhumanly rapid clicking.

我向我的 Cerego 联系人提供了我的一些想法,以尽量减少多选题的一些弊端。因为我的学生在很大程度上对我的恳求充耳不闻,即 "正面"卡片屏幕——只包含问题的屏幕——是真正发生学习的地方,所以可以在该屏幕上设置一个强制性的(或至少是默认的、可选择的)短暂延迟,特别是当应用程序检测到非人类的快速点击时。

Cerego actually asks “Do you know this?” on that screen, giving them a chance to self-assess in the negative without going to the multiple choices, but the vast majority of students never saw this screen as anything but a speed bump to click through.

Cerego 实际上在那个屏幕上问 "你知道这个吗?",给他们一个自我评估的机会,不用去做多选题,但绝大多数学生从来没有把这个屏幕看成是什么,只认为这是一个可以点击的减速带。

My thought was that Cerego could occasionally not show the multiple choice options right away when they click “I Know It”, but instead call their bluff, asking, “Oh? How confident are you?” and prompting them to select a confidence level on a slider bar before showing the choices. Not only might this end the bad habit, it could also provide an opportunity to help them with their credence calibration, a useful skill that might make them better thinkers and learners. I also suggested Cerego might be able to use this data to learn more about a learner and better judge their mastery level through sexy Bayesian wizardry.

我的想法是,当他们点击 "我知道" 时,Cerego 可以偶尔不立即显示多选选项,而是虚张声势地问:"哦? 你有多大信心?"并提示他们在显示选项之前在滑杆上选择一个信心水平。这不仅可以结束这个坏习惯,还可以提供一个机会,帮助他们进行可信度校准,这是一种有用的技能,可以使他们成为更好的思考者和学习者。我还建议 Cerego 也许能够利用这些数据来了解学习者,并通过性感的贝叶斯向导来更好地判断他们的掌握程度。

[My aborted app design would have taken that concept to its logical conclusion: letting trusted users fully self-assess most of the time, but occasionally performing “reality checks” where it made the user respond in a way it could verify. It could then use straightforward Bayesian updates from these checks to decide how often to do them for each user.]

[我中止的应用设计将把这一概念带入其逻辑结论:让受信任的用户在大部分时间内完全自我评估,但偶尔会进行 "现实检查",让用户以它可以验证的方式做出反应。然后,它可以使用这些检查的直接贝叶斯更新来决定对每个用户进行检查的频率。]

New failure modes

新的失败模式

New format, new failure modes:

新格式、新故障模式:

Performative clicking. I would commonly have students who didn’t want the discomfort of getting called to task, but also didn't want to actually do the task, so they would put up a show of productivity, continually clicking random answers over and over again without reading. Others would loiter in the stats screens, play with the cursor, check their grades... anything that wouldn’t require actual thinking.

表演性点击。我通常会遇到一些学生,他们不希望被命令去做任务,但也不想真正做任务,所以他们会摆出一副高效的样子,不看书就不断地反复点击随机答案。其他人则会在统计屏幕上闲逛,玩弄光标,检查他们的成绩......任何不需要实际思考的东西。

Exploits. Some students realized that mindless clicking moved Cerego’s progress bar on their study session forward. In some cases, it even raised their score. One enterprising young man demonstrated this for me, proudly resting a textbook over the Enter key, then kicking back as he “studied” his sets in record time. It was hard to be mad at him, as I could see myself doing the same at his age. Indeed, I was impressed. But he was in no way discouraged by my reminder that I didn’t use Cerego reports for grades, and that his trick wouldn’t leave him any better prepared for the quizzes that counted. (His mind was a steel trap, though; he did just fine.)

漏洞。一些学生意识到,无意识的点击会使 Cerego 的学习进度条向前移动。在某些情况下,这甚至提高了他们的分数。一个有魄力的年轻人向我展示了这一点,他自豪地将一本教科书放在回车键上,然后在创纪录的时间内 "学习" 他的课程。我很难对他生气,因为我可以看到自己在他这个年龄段也会这样做。的确,我被打动了。但是,我提醒他,我并没有用 Cerego 报告来计算成绩,而且他的小把戏也不会让他为重要的测验做更好的准备,他一点也不气馁。(不过,他的思想是一个钢铁陷阱;他做得很好)。

Hunkering. Cerego is set up such that students don’t have new cards added to their rotations until they make an active choice to press a button that does this. Thus, many students would endlessly study only the first twenty cards from the start of the year, never pushing themselves with anything new. In their defense, one of my feedback notes to Cerego was that the UI [in 2017, remember] didn’t make it very clear that they had new material awaiting activation. But even after interventions where I walked them through the process, many of these fox-holed students would fail to activate newer cards on their own initiative.

躲猫猫。Cerego 的设置是这样的:在学生主动选择按下一个按钮之前,他们不会有新的卡片加入到他们的循环中。因此,许多学生会没完没了地学习今年开始的前 20 张卡片,从不用新的东西推动自己。为他们辩护,我给 Cerego 的反馈意见之一是,用户界面[记得是 2017 年]没有很清楚地表明他们有新的材料等待激活。但是,即使在我引导他们完成这一过程的干预下,这些被蒙在鼓里的学生中的许多人还是无法主动激活较新的卡片。

Idleness and moping. Apathy often manifests as lethargy combined with half-hearted complaints, voiced only when confronted, that it’s “too hard” or that “I don’t understand it”. Even though neither of those complaints made much sense when studying limited subsets of word-definition vocab pairs (the most common card set), I still heard both of them regularly from the hibernating bears I dared to poke. (Metaphorically. Never touch students.)

懒惰和闷闷不乐。漠然往往表现为昏昏欲睡,再加上半信半疑的抱怨,只有在面对面时才会说出,"太难了 "或 "我不懂"。尽管这两种抱怨在学习有限的词义配对子集(最常见的卡片集)时都没有什么意义,但我还是经常听到我敢戳冬眠的熊说这两句话。(打个比方,永远不要碰学生。)

This was further evidence of something I already believed: that these complaints, in these contexts, are a means of disincentivizing teachers from bothering them, as opposed to cries for help. After all, if such a student stands by their claim of not understanding it, what is a responsible teacher supposed to do except to stand there and reteach them the whole thing, or schedule one-on-one tutoring, holding their hand with every “I don’t get it” until the work is done for them? If the student had really wanted to understand and do the work, they would have raised their hand as soon as they encountered difficulty instead of trying to be inconspicuous.

这进一步证明了我已经相信的一点:在这种情况下,这些抱怨是为了阻止老师去打扰他们,而不是为了寻求帮助。毕竟,如果这样的学生坚持他们不懂的说法,一个负责任的老师除了站在那里重新教他们整个事情,或者安排一对一的辅导,握着他们的手说每一句 "我不明白",直到他们完成工作,还能做什么呢?如果学生真的想理解并完成工作,他们会在遇到困难时立即举手,而不是试图不引人注意。

[I’ve always been more sympathetic to apathetic students than I probably sound here. Public education demands more directed attention from teenagers than most of them can realistically muster for 35 hours a week.]

[我对漠然的学生总是比我在这里听起来更有同情心。公共教育要求青少年在每周35个小时内有针对性地关注更多问题。]

Dominating the blame game

主导着指责游戏

Teachers are regularly asked by their bosses how they are “differentiating” instruction, adjusting lessons for students across a class’s range of skill levels, learning disabilities, and language deficiencies. They are also asked by parents what their children can do to improve their grade.

教师经常被他们的老板问及他们是如何进行 "差异化" 教学的,为班级中不同技能水平、学习障碍和语言缺陷的学生调整课程。家长们也会问他们,他们的孩子可以做些什么来提高成绩。

Cerego gave me a ready answer to both questions: “Well, in my class we use a free study app that I load with all of the terms, vocab and such that could be on my quizzes. It’s like smart flash cards that let you know when you need to study to avoid forgetting things. They adjust to give you more practice with the things you struggle with. Not only do I provide time to use it during class — even providing a computer if they need it — but it works on any internet device. Students can use it as often they like to be as prepared as they want to be.” Nobody ever complained about this answer, and some were quite impressed with it — more than I was, to be honest.

Cerego 给了我两个问题的现成答案。"好吧,在我的课上,我们使用一个免费的学习应用程序,我把所有可能出现在我的测验中的术语、词汇之类的东西加载进去。它就像智能抽认卡,让你知道你什么时候需要学习,以避免忘记东西。它们会进行调整,让你对你挣扎的东西进行更多的练习。我不仅在课堂上提供时间来使用它——如果他们需要,甚至可以提供一台电脑——而且它可以在任何互联网设备上使用。学生们可以随心所欲地使用它,以做好他们想做的准备"。从来没有人抱怨过这个答案,有些人对它印象相当深刻——说实话,比我印象更深。

I also had powerful ammunition in the all-too-common scenario where, at a meeting with all of the child’s teachers, a parent blames poor grades on the teachers’ not adjusting to their child’s very special needs, instead of on their child’s ridiculously obvious laziness.

我也有了强大的弹药,可以应对非常常见的情况,即在与孩子的所有老师开会时,家长将成绩不佳归咎于老师没有适应孩子的非常特殊的需求,而不是孩子明显的懒惰。

We can’t, of course, just come out and call it like we see it. But we can show parents our data and let them connect the dots. So, in these cases, I would just repeat my “Well, in my class we use a free study app…” spiel, emphasizing the “as prepared as they want to be” part. I would then add, “According to the app, your child has spent [x] minutes studying over the last week, which is about [y]% of the time my average ‘A’ student spent in that same period, and, come to think of it,” I would say, scratching my head for effect, “far less than the time I provide in class for it.”

当然,我们不能直接站出来说我们看到了什么。但我们可以向家长展示我们的数据,让他们把这些点联系起来。因此,在这种情况下,我会重复我的 "嗯,在我的班上,我们使用一个免费的学习应用程序...... "的话语,强调 "他们想做什么就做什么 "的部分。然后我会补充说:"根据这个应用程序,你的孩子在过去一周里花了[x]分钟学习,这大约是我的平均'A'学生在同一时期所花时间的[y]%,而且,想想看,"我会说,为了达到效果,我挠挠头,"远远少于我在课堂上*提供的时间。"

Cue evil gaze from parent to child, squirming discomfort from child, envious awe from my fellow teachers.

父母对孩子恶狠狠的凝视,孩子不安的扭捏,老师们羡慕的敬畏。

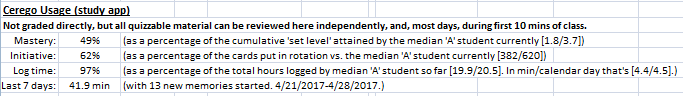

It’s true! Here is a snapshot of one type of output I collected from my report-processing scripts for one of my students. You’re looking at one block of a larger data sheet I brought to parent meetings and included in periodic emails sent home. This one was for a fairly average student who put in the minimum expected time but didn’t push themselves very hard. A slacker's would be more brutal.

这是真的! 下面是我从我的报告处理脚本中收集到的关于我的一个学生的一种输出的快照。你所看到的是一张更大的数据表中的一个区块,我把它带到了家长会上,并包含在定期寄给家庭的电子邮件中。这是一个相当普通的学生,他投入了最低限度的预期时间,但并没有把自己逼得很紧。一个懈怠者的表现会更残酷。

Like I said, absolute dominance.

就像我说的,绝对主导。

But like a lot of games, beating the “blame game” just made me tired of playing it, and ready to move on to something else. The enemy is not the apathetic student. The enemy is Apathy herself. I want to teach the lazy student, not destroy them with my Orwellian gaze.

但就像很多游戏一样,打败 "指责游戏 "只是让我厌倦了玩这个游戏,并准备转到其他方面。敌人不是漠然的学生。敌人是漠然本身。我想教导懒惰的学生,而不是用我奥威尔式的目光摧毁他们。

Results and discussion

结果与讨论

Table

表

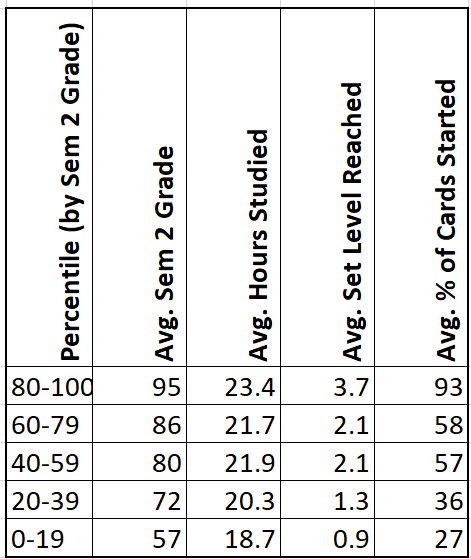

In the following table, n=129, the sum of the 9th and 10th grade students that finished second semester with me. The procedures were identical in both grades, and I didn’t find much reason to divide them, preferring the larger total sample. I then divided the combined sample into quintiles as shown:

在下表中,n=129,是和我一起完成第二学期的九年级和十年级学生的总和。这两个年级的程序是相同的,我觉得没有什么理由要把它们分开,我更喜欢更大的总样本。然后我把合并后的样本分成五等分,如图所示:

The "Sem 2 Grade" is their course grade from just the second semester, but the other stats are all cumulative for the year. (No, I don’t have any state test data for this group, and I never will. Having switched employers, I am not privy to the results, which arrive in late summer or early fall.)

第二学期的成绩 "是他们第二学期的课程成绩,但其他统计数字都是全年的累积成绩。(不,我没有这组学生的州考数据,我也不会有。由于换了雇主,我不知道这些结果,这些结果在夏末秋初到达。)

“Set Level” is Cerego’s signature rating of overall progress and retention, on a 4-point scale.

“设定水平”是 Cerego 对总体进度和保留率的标志性评分,采用 4 分制。

“% of Cards Started” is the fraction of the total cards I had prepared that the students had added into their rotations. (Remember that Cerego did not do this automatically). For 9th graders, there were 648 cards. For 10th grade, there were 749.

"开始卡片的百分比"是我准备的全部卡片中,学生们加入到他们的循环中的部分。(请记住, Cerego 并没有自动做到这一点)。9年级的学生有648张卡片。10年级的学生有749张。

Study time analysis

学习时间分析

As a sanity check, I crudely estimate that we had study time on 160 of our 180 school days, spending an average of 11 minutes each time. That would add up to 29.3 hours of total in-class study time. That the actual averages are lower does not surprise me, due to a combination of absences, roster changes, and start-up times. What we can conclusively say is that there was not a massive amount of outside-of-class study going on.

为了理智起见,我粗略估计,在 180 个教学日中,我们有 160 天的学习时间,每次平均花费 11 分钟。这样算下来,课内学习时间总共为 29.3 小时。实际平均数较低,我并不感到惊讶,这是因为缺勤、花名册变化和启动时间等因素的结合。我们可以断定的是,没有大量的课外学习在进行。

Of course, not all of those logged study minutes were productive study time. It wasn’t always clear to me when Cerego counted a minute towards study vs. idle, or whether it detected idleness at all on the mobile app. Indeed, there were several cases where a student’s mobile app seemed to have logged continual study overnight, and even, in one case, for multiple continuous days. The above chart has not been adjusted for known or unknown anomalies of this kind.

当然,并非所有记录的学习时间都是有效的学习时间。我并不总是清楚 Cerego 何时将一分钟算作学习时间或闲置时间,或者它是否在移动应用程序中检测到闲置时间。事实上,有几个案例中,学生的移动应用程序似乎记录了连续的学习时间,甚至在一个案例中,连续了好几天。上述图表并没有针对这种已知或未知的异常情况进行调整。

Regardless, as you can see, while time spent studying was correlated with performance, there was barely a 25% difference in study time separating the top and bottom grade quintiles. Even this is less exciting than it looks, as the lowest scorers were also more likely to be absent, missing their in-class study time. I have made no effort to adjust for this.

无论如何,正如你所看到的,虽然花在学习上的时间与成绩相关,但在学习时间上,最高和最低年级的五分位数之间几乎没有 25% 的差异。即使是这样,也没有看起来那么激动人心,因为得分最低的人也更有可能缺席,错过了他们的课内学习时间。我没有努力去调整这一点。

One thing you can’t see in that chart is the high variance that existed within the top quintile. In this group, time spent studying varied from 33 hours to 12 — and 12 was the top student! Anecdotally, I perceived two distinct subgroups of high performers: highly motivated learners who had a natural disadvantage, like being a foreign exchange student speaking a second language, and high IQ avid reader types. The former put in far more hours than the latter. In fact, that second group put in less time than the average bottom quintile student.

你在该图表中看不到的一件事是,在最高的五分位中存在的高方差。在这个群体中,学习时间从 33 小时到 12 小时不等——而 12 小时是最优秀的学生! 有趣的是,我认为有两个不同的高分群体:有天然劣势的高积极性的学习者,比如说作为一个讲第二语言的外国交换生,以及高智商的狂热读者。前者投入的时间远远多于后者。事实上,第二类人投入的时间比平均最低五分之一的学生少。

Only a very small number of highly motivated students showed signs of studying over weekends and breaks.

只有极少数积极性很高的学生表现出周末和休息时间学习的迹象。

SRS signal, or just conscientiousness?

SRS 信号,还是只是自觉性?

While you can see a much stronger signal in the “Set Level” and “% of Cards Started” columns, it’s hard to know how much this is just measuring conscientiousness. Good students are going to do what they’re asked to do, and get the good grade no matter what, but this doesn’t mean that what they’re asked to do is always necessary to get the good grade — or that the grade reflects anything worthwhile in the first place.

虽然你可以在 "设定水平 "和 "开始卡片的百分比 "这两栏中看到更强的信号,但很难知道这在多大程度上只是衡量自觉性。好学生会做他们被要求做的事,并且无论如何都会得到好成绩,但这并不意味着他们被要求做的事对得到好成绩总是必要的——或者说,成绩首先反映了任何有价值的东西。

People persons

人

At least a few of the students I could never get to study Cerego were very on-the-ball whenever we did any kind of verbal review.

至少有几个我永远也无法让他们使用 Cerego 学习的学生,每当我们做任何形式的口头复习时都非常上心。

[I’ve seen a lot of this pattern during the pandemic. Students who seemed like inert lumps online, with very low grades, have in many cases returned to the classroom and revealed themselves to be dynamic and invested. An engaging human at the front of the room really is the “value add” of in-person instruction. This is something I encourage my peers to keep in mind whenever deciding between autonomous work and teacher-student interaction.]

[在疫情期间,我已经看到了很多这种模式。那些在网上看起来毫无生气、成绩很差的学生,在很多情况下回到教室后,发现自己很有活力,很投入。在教室前的一个有吸引力的人确实是现场教学的 "附加值"。这是我鼓励我的同行们在决定自主工作和师生互动时要牢记的事情。]

High automaticity in high achievers

高成就者的高度自动化

When it came to automaticity, outlier results were more impressive than ever. The very small number of students at the overlap of highly motivated, highly intelligent, and highly competitive absolutely crushed it in the review game we regularly played at my interactive whiteboard, beating me on several occasions, which almost never happened previously.

当谈到自动化时,离群结果比以往任何时候都更令人印象深刻。在我们经常在我的交互式白板上玩的复习游戏中,极少数处于高度积极性、高度智能和高度竞争的重叠状态的学生绝对是碾压式的,多次击败我,这在以前几乎从未发生过。

Weak transference?

迁移能力弱?

However, transference to other contexts was less evident. In my first report, I had remarked on anecdotal impressions of higher-quality discussion and essay responses from those who had embraced our Anki review, suggesting that they had truly enlarged their lexicon to be able to talk about more complex ideas. I saw less of that this year. I don’t know what that means. It could just be that this mix of students was less open with their thoughts. But I can also see how they may have seen the Cerego universe as distinct from the universe of essay and discussion. Whole-class Anki might be more resistant to this bifurcation by making us say the words out loud to each other, normalizing their use.

然而,移情到其他环境是不太明显的。在我的第一次报告中,我谈到了轶事印象更高质量的讨论和论文回应来自那些接受我们的Anki评论的人,表明他们确实扩大了词汇量,能够谈论更复杂的想法。今年我看到的少了。我不知道那是什么意思。这可能只是因为这些学生对自己的思想不够开放。但我也能看出他们是如何看待塞雷戈宇宙的(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-overlapping_magisteria)来自散文和讨论的世界。全班同学安基可能会更抗拒这种分歧,让我们大声地说出来的话,他们的使用正常化。

然而,转移到其他环境中的情况就不那么明显了。在我的第一份报告中,我曾说过传闻印象,那些接受了我们 Anki 复习的学生的讨论和作文质量更高,这表明他们真正扩大了自己的词汇量,能够谈论更复杂的想法。今年我看到这种情况比较少。我不知道这意味着什么。这可能只是因为这些学生的思想不太开放。但我也可以看到他们可能把 Cerego 的宇宙看作是与论文和讨论不同的宇宙。全班的 Anki 可能对这种分叉更有抵抗力,因为它让我们彼此大声说出这些词,使其使用正常化。

Drama benchmark analysis

戏剧基准分析

To compare methodologies as directly as possible, for a third year running I handled my Drama unit the way I accidentally had during my first year of classroom SRS: some terms taught before the pre-test, most taught after the pre-test, an identical post-test much later, and no review of any of it except through the SRS.

为了尽可能直接地比较方法,我连续第三年按照第一年课堂 SRS 的方式处理我的戏剧单元:一些术语在预考前讲授,大部分在预考后讲授,在很晚的时候进行相同的后考,除了通过SRS,没有对任何内容进行复习。

The overall results in the Drama unit were slightly worse this year. This was surprising. This cohort started lower on the pre-test, which was consistent with my impression of them, but I predicted that we would at least match or exceed last year’s gains, as we had more room to improve. We did not. Retention of some reliable bellwether terms actually dropped prior to the post-test. In picking through individual scores, my impression was that whole-class Anki and independent in-class Cerego were statistically equivalent for motivated learners, but whole-class Anki won easily with less motivated learners. As always, there were plenty of truly unmotivated students who got nothing from either method.

今年戏剧组的整体成绩略差。这很令人惊讶。这批学生在测试前的起点较低,这与我对他们的印象一致,但我预测我们至少会赶上或超过去年的成绩,因为我们有更大的进步空间。我们没有做到。一些可靠的风向标术语的保留率在后考前实际上是下降的。在挑选个人分数时,我的印象是,对于积极的学习者来说,全班 Anki 和独立的课内 Cerego 在统计学上是相等的,但是对于积极性不高的学习者来说,全班 Anki 很容易获胜。和往常一样,有很多真正没有动力的学生在两种方法中都一无所获。

I tried to tease this out even further. This was pretty unscientific, but I took the pre and post-test scores of twenty students from last year, and aligned them individually to students from this year with similar pre-test scores and, in my view, similar work ethics. Highly motivated students starting very low may have done slightly better with Cerego than with Anki, but poorly motivated students starting low did somewhat better with Anki.

我试图进一步弄清这一点。这是很不科学的,但是我把去年 20 个学生的测试前和测试后的分数,分别与今年测试前分数相近的学生进行对比,在我看来,他们的工作态度也很相似。积极性很高的学生在使用 Cerego 时可能比使用 Anki 时成绩略好,但积极性不高的学生在使用 Anki 时成绩略好。

I’m sure a lot of this came down to how Cerego makes new card sets “opt-in”. Students of lower motivation were less likely to encounter the Drama terms in their study rotation at all!

我确信这很大程度上归结于 Cerego 如何“选择加入”新牌组。积极性较低的学生在他们的学习轮换中根本不可能遇到戏剧术语!

Phone vs. Computer seemed to make a difference here, too. Stuck with a very visible PC, some low performers would occasionally have good days and get in a groove. The ones glued to their phones found anything to do except Cerego.

手机和电脑在这里似乎也有区别。坚持用非常显眼的电脑,一些表现不佳的人偶尔会有好日子,进入状态。而那些一直使用手机的人则发现除了 Cerego 之外,什么都可以做。

Conclusions (2017)

结论(2017)

If I see students as being ultimately responsible for their own learning, independent Cerego is the fairer approach that will help students get what they “deserve”. If I see things more pragmatically and utilitarian (as I do), the numbers favor the whole-class Anki approach. And yet...

如果我认为学生最终要对自己的学习负责,那么独立的 Cerego 是更公平的方法,可以帮助学生获得他们 "应得的" 东西。如果我把事情看得更实际、更功利(就像我一样),那么数字就有利于全班的 Anki 方法。然而...

If I were staying at that school, with my classroom computers, I would have tried to get the best of both worlds. It was my plan to use Cerego again — having already done most of the legwork — and try to make it friendlier, with more teacher interaction, supplementing with some whole-class Anki. I would have pushed Cerego’s developers to make some of my most wanted changes, and I would have pushed myself to cut back on the number of cards I used.

如果我留在那所学校,用我的教室电脑,我就会试图获得两个世界的最好结果。我计划再次使用Cerego——我已经做了大部分的工作——并试图使它更友好,有更多的教师互动,并辅以一些全班的 Anki。我将推动 Cerego 的开发者做出一些我最想要的改变,我也将推动自己减少我使用的卡片数量。

But it’s moot, now. I won’t have computers at my new school. And part of the reason I left was because I didn’t like the feel of the groove I was settling into.

但现在已经没有意义了。我在新学校不会有电脑。而我离开的部分原因是我不喜欢我所处的环境的感觉。

Whole-class Anki review wins for simplicity and camaraderie. Cerego wins for surveillance and power. Which would you want to see stamping on a teenage face forever?

全班的 Anki 复习因其简单性和友情而获胜。Cerego 以监视和权力取胜。你希望看到哪一个永远印在青少年的脸上?

Trick question! It’s not nice to stamp on faces. I feel like I’ve been pushing SRS too far past the point of diminishing returns, and I don’t know why it has become an annual tradition for me to vow to cut back next year and then fail to do so. I should probably break that cycle. Apathy is the enemy, and she remains unbowed. I’ve been looking for a technological fix, but I think the solution is, at best, only partly technological.

骗人的问题! 在脸上盖章是不好的。我觉得我已经把 SRS 推得太远了,超过了收益递减的程度,我不知道为什么这已经成为我每年的传统,我发誓明年要减少,然后又做不到了。我也许应该打破这个循环。漠然是敌人,而她仍然不屈服。我一直在寻找一个技术解决方案,但我认为这个解决方案充其量只是部分技术。

[My notes here spiraled off into very technological solutions (sigh) to add to my dream SRS+ app, which I had already postponed again but still wasn’t ready to abandon. I suppose I can give myself a little credit for brainstorming features to encourage human interaction and conceptual connections. Eventually, my notes came back to some thoughts about what makes a class thrive, which I have translated into coherent sentences below.]

[我在这里的笔记旋即变成了非常技术性的解决方案(叹气),以添加到我梦想的 SRS+ 应用中,我已经再次推迟了,但仍然不准备放弃。我想我可以给自己一点赞誉,因为我想通过头脑风暴来鼓励人类互动和概念联系。最终,我的笔记又回到了关于什么使一个班级蓬勃发展的一些想法上,我把这些想法翻译成了以下连贯的句子。]

From a scalability standpoint, it’s nice that something like Cerego doesn’t depend on a teacher’s charm the way my whole-class Anki approach does. Teachers could do a lot worse than a standardized pack of quality Cerego sets that reinforce matching cookie-cutter lessons. But couldn’t teachers also do better? I think I could do better. Cerego and Canvas quizzes create distance between me and my students. But I want to bring us closer and dial up the enthusiasm.

从可扩展性的角度来看,像 Cerego 这样的东西不像我的全班 Anki 方法那样依赖于教师的魅力,这很好。教师可以做得更多,而不是用一包标准化的高质量的 Cerego 套装来加强与之相匹配的 cookie-cutter 课程。但是老师们难道不能做得更好吗?我认为我可以做得更好。Cerego 和 Canvas 测验在我和我的学生之间制造了距离。但我想拉近我们之间的距离,提高我们的热情。

I don’t think gamification is the answer. I’ve been noticing that the appeal of games is pretty niche, failing to capture many from the apathetic middle, and then for the wrong reasons, with the wrong incentives.

我不认为游戏化是答案。我一直注意到,游戏的吸引力是相当小众的,未能从漠然的中间人群中抓住许多人,然后出于错误的原因,用错误的激励措施。

So what would work?

那么什么能起作用呢?

In education research, it always looks like everything works at least a little bit. This is probably a combination of publication bias and the fact that teachers sometimes get excited to try something new. Excitement is infectious. This gets students more engaged, which then improves outcomes. My early success with classroom SRS — and subsequent disappointments — would certainly fit that pattern.

在教育研究中,每件事情看起来都至少有一点效果。这可能是出版偏见和教师有时对尝试新事物感到兴奋的综合原因。兴奋是有感染力的。这让学生更加投入,从而提高了效果。我在课堂 SRS 方面的早期成功——以及随后的失望——肯定符合这种模式。

Maybe I should make a point of trying new things each year for the explicit purpose of exploiting the excitement factor? How would I explain that to my bosses? “Well, I deliberately diverged from the curriculum and accepted best practice because I grew weary of them.”

也许我应该每年都尝试新的东西,目的很明确,那就是利用兴奋因素?我将如何向我的老板们解释?"好吧,我故意偏离课程,接受最佳实践,因为我对它们越来越厌倦了。"

[Yes, actually. My new bosses are great that way.]

[是的,实际上,我的新老板们都是这样的好手。]

Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis (2021)

论文、反论、综述(2021)

As a student of storytelling, I can’t help but find an arc to my fourteen years of teaching up to this point.

作为一个讲故事的学生,我不禁发现我到现在为止的十四年教学生涯有一个转折点。